A groundbreaking study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association has unveiled a concerning revelation: anger, unlike other common negative emotions such as sadness or anxiety, significantly diminishes blood vessels’ ability to dilate, posing a potential threat to vascular health and, consequently, heart health.

Led by Dr. Daichi Shimbo, a Cardiologist and Professor of Medicine at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, the research emphasizes the intricate relationship between mental and physical health. “We found that anger, but not the other emotions that we studied, had an adverse impact on vascular health. So there’s something about anger that’s what I call ‘cardiotoxic.’ So it’s a possible mechanism of why feelings of anger may be associated with increased heart disease risk,” explained Dr. Shimbo.

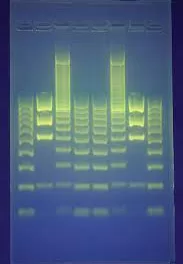

The study, which involved 280 healthy adult participants, focused on exploring the impact of various emotional states on endothelial cell health—a crucial indicator of vascular well-being. Endothelial cells line the interior of blood vessels and play a pivotal role in regulating healthy blood flow throughout the body. Participants were randomly assigned to recall tasks associated with anger, anxiety, sadness, or a neutral emotional state.

The results were striking. While emotions like anxiety and sadness did not exhibit adverse effects on vascular health, anger significantly impaired the blood vessels’ ability to dilate, consequently restricting blood flow. This impairment persisted for up to forty minutes following the recall exercise, highlighting the lingering impact of anger on vascular function.

Dr. Shimbo’s research underscores the need to distinguish between various negative emotions when assessing their impact on heart health. “Our data suggest that maybe the mechanisms that explain anxiety and sadness in heart disease risk are different than those that explain anger. So it tells us: be careful about lumping different negative emotions in the same bucket,” he cautioned.

This study builds upon previous research highlighting the detrimental effects of anger on cardiovascular health. Dr. David Spiegel, Associate Chair of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine, emphasized the profound physiological changes triggered by anger. “It has a lot to do with threat. It’s both experiencing threat and expressing threat to others. It’s triggered in the base of the brain, the amygdala, and it stimulates sympathetic arousal that is preparing the body to fight or flee,” explained Dr. Spiegel.

The findings serve as a sobering reminder of the interconnectedness between mental and physical well-being. As Dr. Shimbo aptly summarized, “Your emotional state can affect the health of your body.” With anger emerging as a potent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, understanding and managing this emotion could prove pivotal in safeguarding heart health in the long term.