A groundbreaking study led by the Monell Chemical Senses Center has revealed significant differences in how people perceive the bitterness of medicines based on their ancestry. The research, published in Chemical Senses, suggests that genetic variations play a key role in individual responses to bitter-tasting drugs and their modifiers.

Understanding Bitterness in Medicine

Many essential medicines are notoriously bitter, which can lead to reluctance in taking them. To improve palatability, pharmaceutical companies often add sweeteners and flavor modifiers. However, the effectiveness of these additives varies from person to person, and now, researchers have uncovered genetic factors that may explain why.

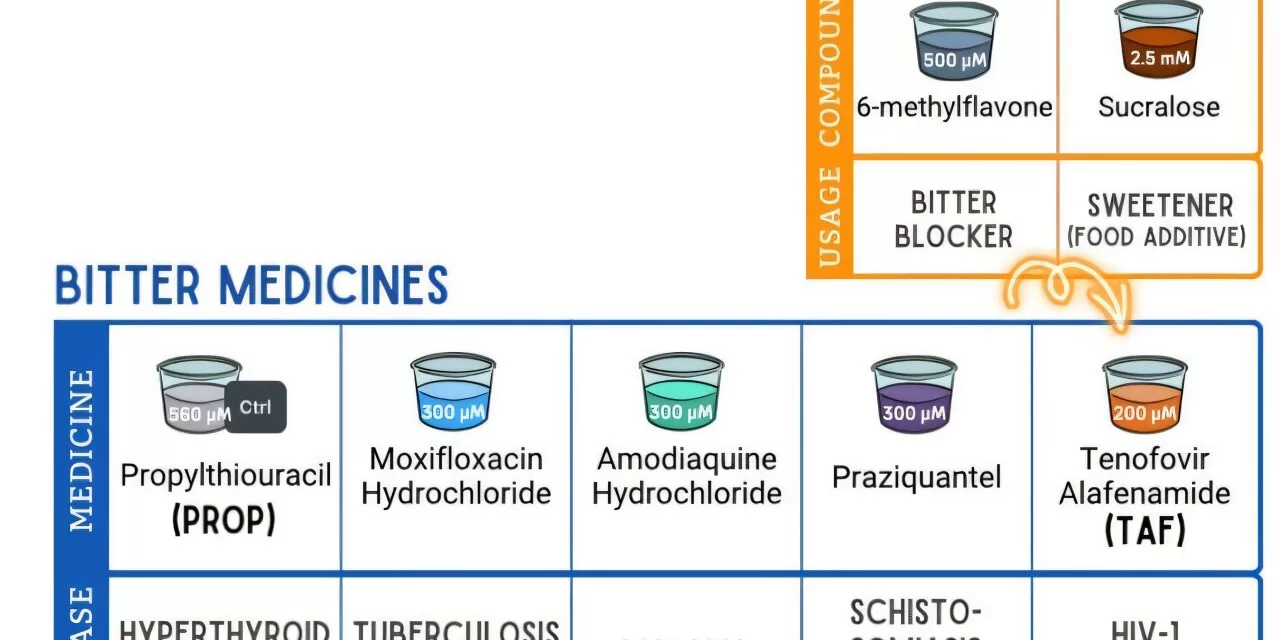

The study assessed 338 adults from diverse backgrounds, including European descent and recent immigrants to the U.S. and Canada from Asia, South Asia, and Africa. Participants rated the bitterness of five commonly used drugs—tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), moxifloxacin, praziquantel, amodiaquine, and propylthiouracil (PROP)—as well as two bitterness modifiers: sucralose and 6-methylflavone.

Key Findings: Genetic Influence on Taste Perception

The study found that while individual bitterness sensitivity varied widely within each ancestry group, 40% of the tested medicines exhibited differences in perceived bitterness based on ancestry.

- PROP, used for hyperthyroidism, was rated as significantly more bitter by participants of Asian ancestry compared to other groups.

- Amodiaquine, a malaria drug, was found to be more bitter for individuals of European ancestry than for those of African ancestry.

- Sucralose, a commonly used sweetener, was more effective in reducing bitterness for African participants compared to Asian participants when added to TAF.

These findings align with previous research on genetic variants of the TAS2R38 taste receptor, which influences how people perceive bitterness.

Implications for Medicine Formulation

“Our findings may help guide the formulation of bad-tasting medicines to meet the needs of those most sensitive to them,” said lead author Dr. Ha Nguyen, a postdoctoral fellow at Monell.

Bitterness can serve as a protective mechanism to prevent accidental poisoning, but when it comes to life-saving treatments, an unpleasant taste can deter patients from completing their prescribed doses. Dr. Dani Reed, the study’s senior author and Monell’s Chief Science Officer, emphasized the clinical impact of this issue: “Poor palatability can be a serious barrier to treatment adherence, particularly in low-resource settings where every dose matters.”

The research highlights the importance of personalized medicine approaches, particularly in drug formulation. By considering genetic and ancestry-related differences, pharmaceutical companies could develop more effective bitterness-masking strategies, improving medication compliance and health outcomes globally.

Future Directions

As scientists continue to explore the genetic basis of taste perception, further studies may lead to customized pharmaceutical formulations that cater to different populations. This research paves the way for a future where medicine is not only effective but also more palatable for all patients.

Disclaimer

The findings of this study are based on research conducted by the Monell Chemical Senses Center and published in Chemical Senses. While the study provides valuable insights into genetic influences on taste perception, individual responses to medicine can vary. Patients should always consult healthcare professionals before making decisions regarding their medication.