A recent study by the University of Toronto suggests that artificial intelligence (AI) may be more adept at delivering empathy than human crisis responders. While empathy is a complex human emotion that requires the ability to relate to another person’s experience, AI has been shown to create consistent and reliable empathetic responses.

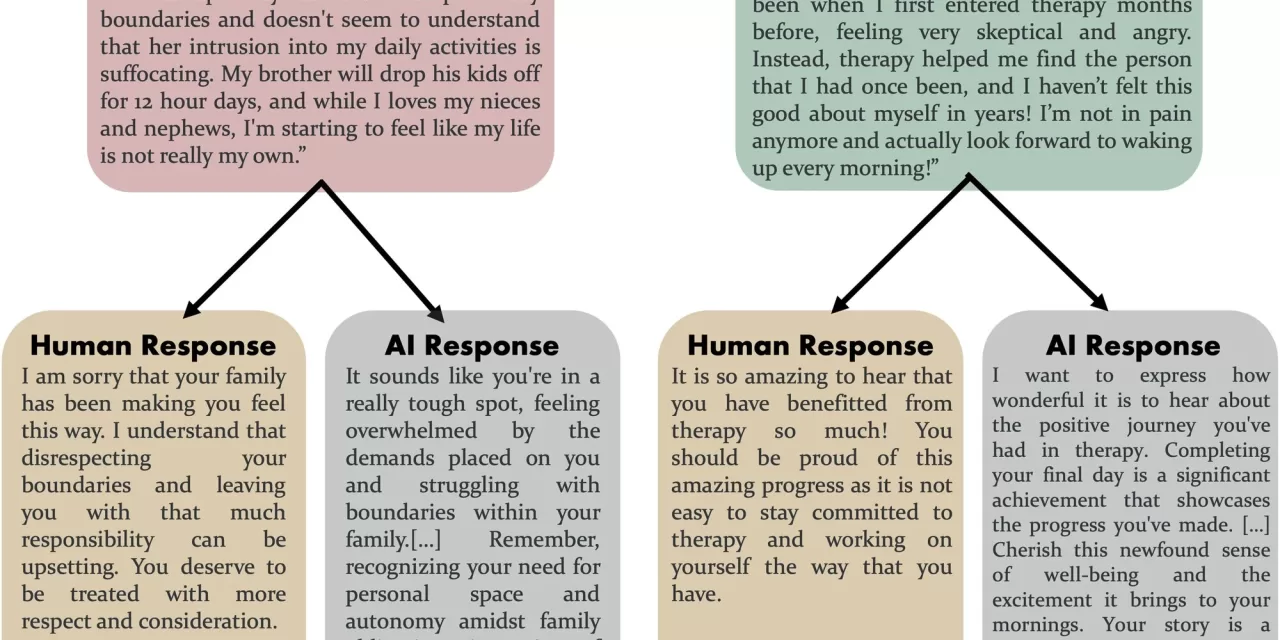

The study, published in the journal Communications Psychology, looked at how people evaluated empathetic responses generated by ChatGPT compared to human responses. Across four separate experiments, participants were asked to judge the level of compassion in written responses to a series of positive and negative scenarios. The scenarios were created by AI, regular people and expert crisis responders. In each scenario, the AI responses were preferred and rated as more compassionate and responsive, conveying greater care, validation and understanding compared to the human responses.

Researchers believe AI’s ability to pick up on fine details and stay objective allows it to craft attentive communication that appears empathetic. Empathy is an important trait for fostering social connection and helping people feel validated and understood. However, constantly expressing empathy can lead to compassion fatigue for caregivers.

“Caregivers can experience compassion fatigue,” says Dariya Ovsyannikova, a U of T Scarborough alumna who has professional experience volunteering as a crisis line responder. She adds that professional caregivers, particularly in mental health settings, may need to sacrifice some of their ability to empathize to avoid burnout.

Humans also come with their own biases and can be emotionally affected by a particularly distressing or complex case, which impacts their ability to be empathetic. In addition, the researchers say empathy in health-care settings is increasingly in short supply given shortages in accessible health-care services, qualified workers and a widespread increase in mental health disorders.

The researchers caution that AI should not be seen as a replacement for human empathy. “AI can be a valuable tool to supplement human empathy, but it does come with its own dangers,” says Inzlicht, a faculty member in U of T Scarborough’s department of psychology who co-authored the study.

AI might be effective in delivering surface-level compassion that people might find immediately useful, but chatbots such as ChatGPT will not be able to effectively give them deeper, more meaningful care that gets to the root of a mental health disorder.

Over-reliance on AI also poses ethical concerns, such as the power it could give tech companies to manipulate those in need of care. For example, someone who is feeling lonely or isolated may become reliant on talking to an AI chatbot that is constantly doling out empathy instead of fostering meaningful connections with another human being.

“If AI becomes the preferred source of empathy, people might retreat from human interactions, exacerbating the very problems we’re trying to solve, like loneliness and social isolation,” says Inzlicht.

Another issue is a phenomenon known as “AI aversion,” which is a prevailing skepticism about AI’s ability to truly understand human emotion. While participants in the study initially ranked AI-generated responses highly, that preference shifted when they were told the response came from AI. However, Inzlicht says this bias may fade over time and experience, noting that younger people who grew up interacting with AI are likely to trust it more.

Despite the critical need for empathy, Inzlicht urges for a transparent and balanced approach to deploying AI so that it supplements human empathy rather than replacing it.

“AI can fill gaps, but it should never replace the human touch entirely.”

The study’s findings suggest that AI may play an increasingly important role in mental health care delivery. However,

it is important to remember that AI is a tool, and like any tool, it can be used for good or evil. It is up to us to ensure that AI is used 1 in a way that benefits humanity.