Researchers at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) have made a groundbreaking discovery that could transform the way sepsis is treated, potentially saving millions of lives annually. In a study published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, the team revealed how a molecule found on certain bacteria may play a significant role in blood clotting during sepsis, a life-threatening condition that causes approximately 8 million deaths per year.

Sepsis occurs when the body’s immune response to an infection spirals out of control, resulting in widespread inflammation, organ failure, and complications such as excessive blood clotting. While previous research has focused on antibiotics and supportive care, treatment options have remained limited, with little progress in developing targeted therapies.

The research team at OHSU, led by Dr. Owen McCarty, a professor of biomedical engineering, investigated the role of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a molecule found on the surface of certain bacteria like E. coli. They discovered that LPS directly activates proteins in the blood that trigger clotting. This can block blood flow and damage vital organs. One specific type of LPS, called O26:B6, was found to be particularly effective at initiating this dangerous clotting reaction.

Dr. Joseph Shatzel, a physician-scientist specializing in clotting disorders at OHSU, explained that sepsis creates a dangerous imbalance in the body’s blood clotting systems. “The systems that control blood clotting and bleeding become dangerously unbalanced,” he said. “Our group has focused on the contact activation system, an area that has been largely ignored in the past.”

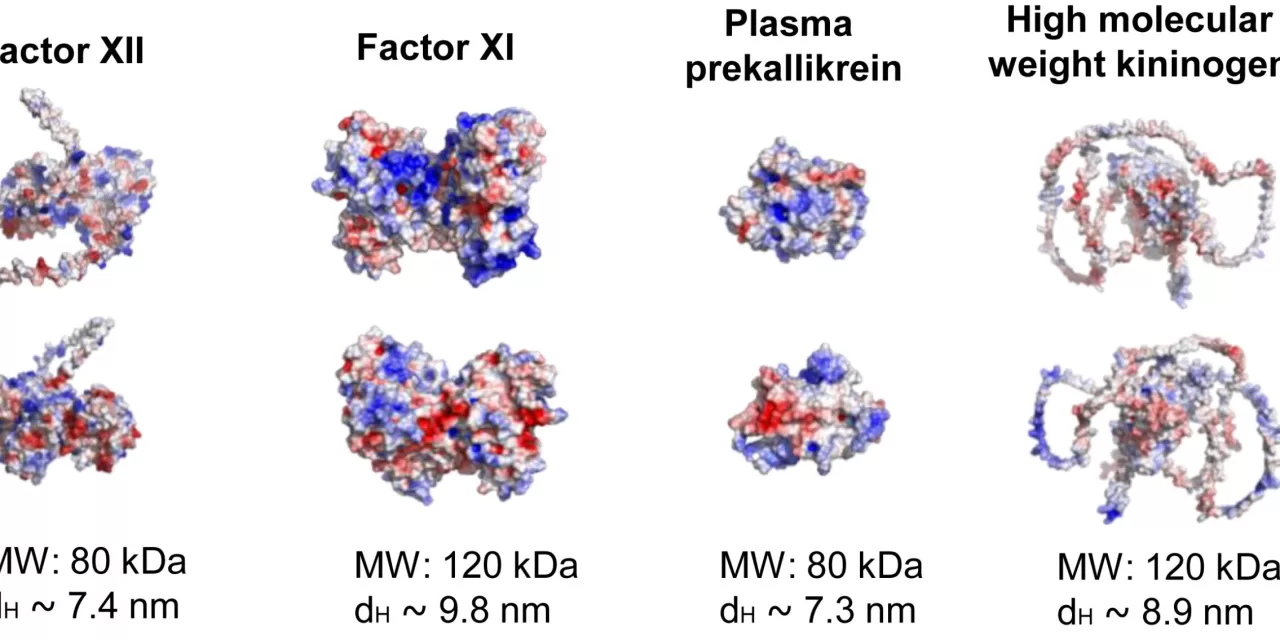

The researchers conducted studies in nonhuman primates, showing that bacteria containing LPS quickly activated the clotting system, including coagulation proteins like factor XII, which is believed to start the clotting process. Interestingly, people born without factor XII do not experience abnormal bleeding, making it an ideal target for therapies to prevent dangerous clotting without increasing the risk of bleeding.

Dr. André Lira, a postdoctoral scholar and lead author of the study, explained that understanding how the physical properties of bacterial surfaces trigger the clotting system could lead to more precise treatments for sepsis. “Different strains of bacteria can behave differently, and understanding this variability is key to developing targeted therapies,” Lira said.

The team is working on experimental treatments aimed at blocking factor XII activity, including antibodies designed to prevent the clotting cascade triggered by LPS. Early-stage clinical trials and animal models have shown promising results, suggesting these antibodies could stop sepsis-induced clotting without impairing the body’s ability to heal.

“The potential impact of this research is immense,” said McCarty. “By preventing dangerous clots in sepsis patients, we could dramatically improve survival rates and outcomes for critically ill individuals.”

Despite these promising findings, Dr. Shatzel emphasized that there is still a long way to go. “The mortality rate of sepsis in the United States can be as high as 50%, and there have been no major breakthroughs in decades. This research could be a game-changer.”

The study’s interdisciplinary approach, combining the expertise of basic scientists, clinicians, and engineers, has been instrumental in driving the team’s innovative work. “We have basic scientists like André, who think about the physics of how bacteria interact with blood, and clinicians like Joe, who see the real-world challenges in the ICU,” McCarty said.

With ongoing research, clinical trials, and grant applications, the team at OHSU is hopeful that their discoveries will lead to better treatments for sepsis and ultimately save lives. “We’re excited about the potential to help patients,” Lira said. “It’s a long journey, but the possibility of making a real difference drives us forward.”

Co-authors of the study include Berk Taskin, Cristina Puy Garcia, Jiaqing Pang, Joseph E. Aslan, Christina U. Lorentz, and Erik I. Tucker from OHSU, as well as researchers from the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Case Western Reserve University, and Vanderbilt University Medical Center.