A groundbreaking study from the McGovern Institute for Brain Research has revealed that children’s personal interests significantly influence how their brains process language. The study, published in Imaging Neuroscience, marks a significant step forward in personalized brain research, demonstrating the potential of tailoring research stimuli to individual interests in order to improve our understanding of language processing in the brain.

Led by Anila D’Mello, a former postdoctoral researcher at McGovern and now an assistant professor at the University of Texas, the study challenges the traditional approach in neuroscience. In contrast to standard studies, which typically present all participants with the same stimuli, this research personalized content according to each child’s unique interests. The results were clear: children showed stronger and more consistent brain activity in language regions when listening to stories tailored to their preferences.

“This study marks a paradigm shift,” said John Gabrieli, the senior author of the paper and a professor at MIT. “By considering personal interests, we were able to enhance the engagement of the brain’s language areas, showing that personalization is a powerful strategy in neuroscience.”

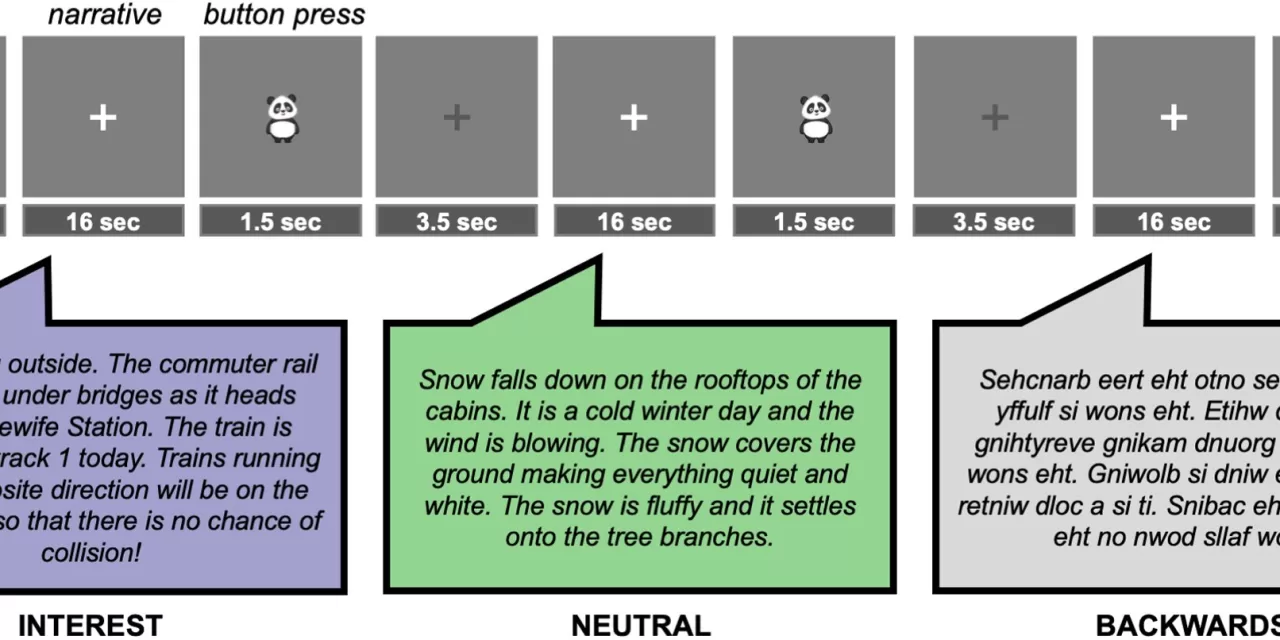

The study was conducted with 20 children, who were exposed to audio stories on topics they were passionate about, ranging from baseball and “Minecraft” to musicals and train lines. These personalized stories were compared to more generic stories about nature, a subject none of the children showed strong interest in. The children’s brain activity was measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which captures real-time brain responses based on blood flow.

The findings revealed that when the children listened to stories that aligned with their interests, there was a marked increase in neural responses in regions of the brain associated with language. More importantly, the brain activation patterns of the children were much more consistent when they engaged with interest-based content, as opposed to the generic stories.

“Interest-driven content not only increases the magnitude of neural responses but also enhances the consistency of those responses across different individuals,” said co-first author Halie Olson, a postdoc at the McGovern Institute. “This shows that personal interests play a crucial role in language processing, and using them in studies can provide deeper insights into brain activity.”

The study also highlighted activation in brain regions related to reward and self-reflection, reinforcing the idea that interests make learning more engaging and rewarding. “When children engage with content they find motivating, their brains light up not just in language areas but in regions linked to enjoyment and self-relevant thinking,” noted D’Mello.

This innovative approach holds promise for future research, particularly in understanding language processing in neurodivergent populations such as children with autism. The researchers are already applying these methods to study language development in these groups.

Gabrieli emphasized that this research could pave the way for more personalized neuroscience studies. “By tailoring stimuli to individual interests, we not only increase the accuracy of our findings but also respect the diversity of human experience, which is often overlooked in traditional research.”

As neuroscience moves towards a more individualized approach, this study provides a critical foundation for future investigations into how personalized experiences shape the brain’s ability to process complex functions like language.

For further reading, see Personalized neuroimaging reveals the impact of children’s interests on language processing in the brain, published in Imaging Neuroscience (2024), DOI: 10.1162/imag_a_00339.