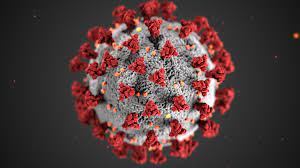

As the world moves beyond the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns about the next big infectious disease outbreak are growing. Public health officials are closely monitoring several pathogens that are likely to present significant challenges in the coming years, including malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis, which together kill around 2 million people annually. However, it is an influenza virus—H5N1, also known as bird flu—that is currently causing the greatest concern for 2025.

Bird flu, which primarily affects wild and domestic birds, has recently been detected in mammals, including dairy cattle in the United States and horses in Mongolia. This spread to other animals raises alarms that the virus could eventually jump to humans, as has happened with previous strains of influenza. Already, 61 human cases of bird flu have been reported in the United States in 2025, a sharp increase compared to just two cases in the previous two years.

The cause for concern is the virus’s high mortality rate among humans, standing at 30%. While H5N1 does not currently spread easily from human to human—because it is adapted to bird sialic receptors, not human ones—a recent study revealed that a single genetic mutation could enable the virus to spread more efficiently between humans. If this mutation occurs, it could pave the way for a pandemic.

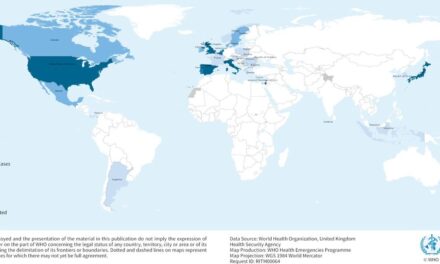

Governments are preparing for this potential threat, with many countries, including the UK, securing stockpiles of H5N1 vaccines. The UK, for instance, has already purchased 5 million doses to prepare for any eventual outbreaks. However, even without the ability to transmit easily between humans, H5N1 is expected to continue causing significant animal health issues in 2025, affecting the poultry industry and other sectors related to animal agriculture. This not only raises animal welfare concerns but also threatens food security and could lead to economic disruptions.

The growing threat of H5N1 highlights the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health—a concept known as “one health.” Efforts to prevent disease outbreaks in animals and the environment can help prevent the spread of pathogens to humans. Conversely, monitoring and controlling infectious diseases in humans can also protect animal and environmental health.

In addition to emerging threats like bird flu, public health experts remain focused on ongoing “slow pandemics” such as malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis. While these diseases may not have the immediate global impact of a new viral outbreak, they continue to claim millions of lives each year, requiring ongoing attention and intervention.

As we head into 2025, the global health community must remain vigilant, balancing efforts to combat existing infectious diseases with proactive measures to address new threats before they evolve into pandemics. The coming year will undoubtedly test our preparedness and response capabilities in unprecedented ways.