December 25, 2024

Scientists at the Bose Institute, an autonomous research organization under the Department of Science and Technology (DST), have made a groundbreaking discovery about how some of the earliest forms of life on Earth survive in extreme conditions. Their study focuses on archaea, a group of microorganisms belonging to one of the three primary domains of life, known for their ability to thrive in some of the most inhospitable environments on the planet.

The research, led by Dr. Abhrajyoti Ghosh from the Department of Biological Sciences, investigates how archaea utilize toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems to adapt to harsh conditions, such as extreme heat. The findings, recently published in the journal mBio, provide valuable insights into the resilience of these microorganisms, with implications for understanding life’s adaptability and potential survival strategies in extraterrestrial environments.

Exploring the Heat-Loving Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius

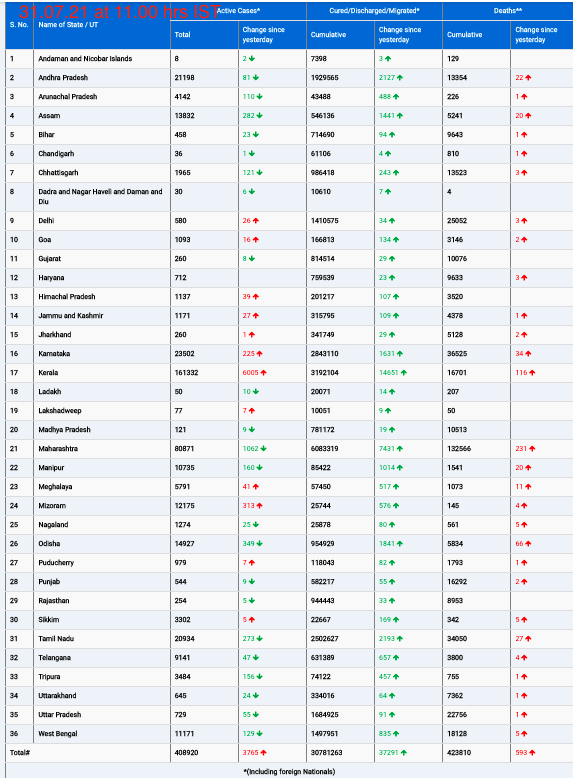

The team concentrated their efforts on Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, a type of archaea that thrives in volcanic hot springs with temperatures reaching up to 90°C. These organisms are found in environments like Barren Island in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India, as well as other volcanic areas worldwide. The research focused on the VapBC4 TA system within this archaeon, a mechanism that plays a critical role during heat stress.

Dr. Ghosh’s team discovered that the VapC4 toxin in this system performs several vital functions, including halting protein production, promoting the formation of resilient cells, and influencing the development of biofilms—structures that provide additional protection to microorganisms. The study highlights how the VapC4 toxin is regulated by its antitoxin counterpart, VapB4, under normal conditions. However, when heat stress occurs, an unidentified stress-activated protease breaks down VapB4, freeing VapC4 to initiate its survival functions.

The Role of “Persister Cells” in Survival

One of the key findings was how S. acidocaldarius forms “persister cells” during stress. These cells enter a dormant state, conserving energy and halting the production of proteins that might be damaged by the extreme heat. This dormancy allows the organism to endure the harsh environment until conditions become more favorable.

“This mechanism is a remarkable example of nature’s ingenuity in ensuring survival against all odds,” Dr. Ghosh said. “It not only helps us understand how ancient life evolved but also offers potential applications in biotechnology and medicine, particularly in understanding microbial persistence in extreme conditions.”

Broader Implications

Archaea, meaning “ancient things” in Greek, are considered one of the oldest life forms on Earth, providing a window into the early evolution of life. Their ability to survive in extreme conditions, such as boiling hot springs, acidic waters, and deep-sea vents, makes them ideal candidates for studying the limits of life on Earth—and possibly other planets.

The findings could also inspire novel strategies for developing heat-resistant enzymes and biotechnological tools, as well as offering insights into combating microbial persistence in industrial and medical settings.

This research underscores the importance of studying ancient microorganisms like archaea, not just for their role in Earth’s history, but for their potential to unlock secrets about life’s resilience and adaptability in extreme conditions.