Stanford Medicine researchers and their international collaborators have unveiled a transformative understanding of cancer development through three studies that challenge fundamental genetic principles. These studies, published in Nature, spotlight the previously overlooked role of extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) in driving various cancers, upending Mendel’s foundational genetic law. Spearheaded by Stanford’s Dr. Paul Mischel and Dr. Howard Chang, the findings offer insights into cancer mechanisms and introduce promising therapeutic approaches.

The discovery centers around ecDNA—small circular DNA segments existing outside chromosomes. Historically deemed insignificant, ecDNA is now shown to be present in 17.1% of tumors across nearly 15,000 cancer cases analyzed. This high prevalence underscores ecDNA’s role in cancer aggression, especially following chemotherapy or targeted treatments. In many cases, ecDNAs contain oncogenes, which fuel rapid cancer cell growth, and immune-suppressing genes, which shield tumors from the body’s defenses.

“This is a paradigm shift in how we understand cancer,” said Dr. Mischel, co-senior author of the three studies and leader of the eDyNAmiC research team, which received a $25 million Cancer Grand Challenges grant in 2022. “Each paper contributes uniquely to our knowledge, but collectively, they represent a pivotal change in our view of cancer initiation and progression.”

A Break from Mendel’s Law

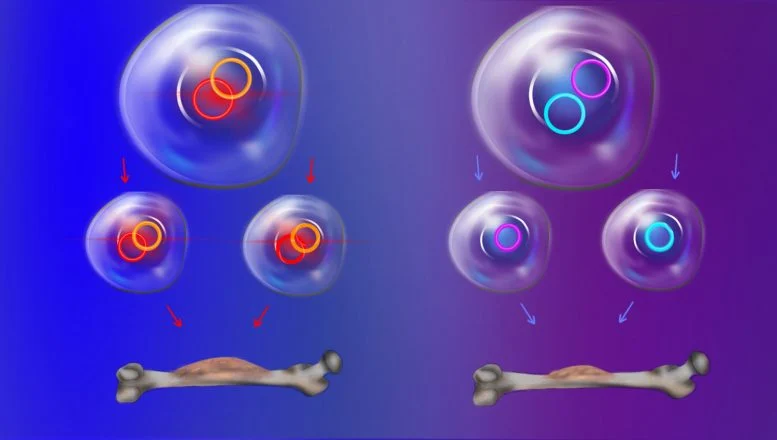

One of the most surprising findings involves the ecDNA’s inheritance pattern, which contradicts Gregor Mendel’s 19th-century law of independent assortment. Typically, genes are inherited independently unless physically connected on chromosomes, but ecDNA defies this rule. The Stanford team discovered that, unlike standard chromosomes, ecDNA transcription—a process crucial for protein production—continues unbroken during cell division, leading ecDNAs to cluster together and pass as multi-circle units to daughter cells.

“This discovery redefines our understanding of genetic inheritance,” Dr. Chang explained. “Cells inheriting advantageous ecDNA combinations gain a ‘jackpot hand,’ boosting their survival in hostile environments like those created by chemotherapy.” Such events are rare under normal genetics but occur frequently in cancer cells, giving them a competitive edge.

Targeting a Cancer Weakness

While these jackpot ecDNA combinations make tumors resilient, they also create vulnerabilities. A third study led by the Stanford team showed that disrupting a protein checkpoint, CHK1, could selectively kill ecDNA-laden cancer cells. Blocking CHK1 caused fatal DNA replication-transcription conflicts, stopping cancer cells from dividing. This strategy proved effective in lab-grown cells and animal models, halting tumor growth.

“The ecDNAs drive cancers to become transcription-addicted,” Dr. Chang said. “By targeting this addiction, we turned an advantage into a lethal flaw.” Encouraged by these results, the researchers have advanced CHK1 inhibitors into early clinical trials for cancers with high ecDNA counts, aiming to use this vulnerability to combat aggressive cancer types.

A New Era in Cancer Research

The collective research by Drs. Mischel, Chang, and their global collaborators marks a new direction in cancer genetics and therapy. “Science is a collaborative pursuit,” Dr. Mischel noted. “Through data and insight from diverse sources, we’re proving these findings are real and important, and we’re committed to pushing this knowledge forward to benefit patients.”

As the trials continue, the findings herald a shift toward ecDNA-targeted treatments, offering hope for tackling one of cancer’s toughest challenges.