January 22, 2024

In a macabre turn of events, investigators in Australia were met with an unexpected challenge when they discovered the body of a 69-year-old man suspected to have been dead for days. Instead of the anticipated gruesome scene, approximately 30 cats flooded out of the residence. Inside, the man’s body lay on the floor, his face gnawed down to the skull, and his heart and lungs missing. The bizarre incident sheds light on the potential issue of pets scavenging on human remains, presenting significant challenges for forensic investigations.

The Australian case is not isolated, and experts suggest that pet scavenging may be more common than previously acknowledged. Carolyn Rando, a forensic anthropologist at University College London, remarks, “I think we have to come to the conclusion that our pets will eat us. It’s just a fact of life.” This poses complications for investigators trying to ascertain details of a death, such as the involvement of toxins or evidence of sexual crimes.

To address this challenge, a recent study in Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology proposes ways for detectives to determine whether an animal scavenged a body and what kind of animal it was. The study, conducted by anthropologists at the University of Bern, compiles published reports on corpse scavenging by cats, dogs, and even a hamster. The researchers also review seven recent cases in Switzerland where pet scavenging caused difficulties for investigators.

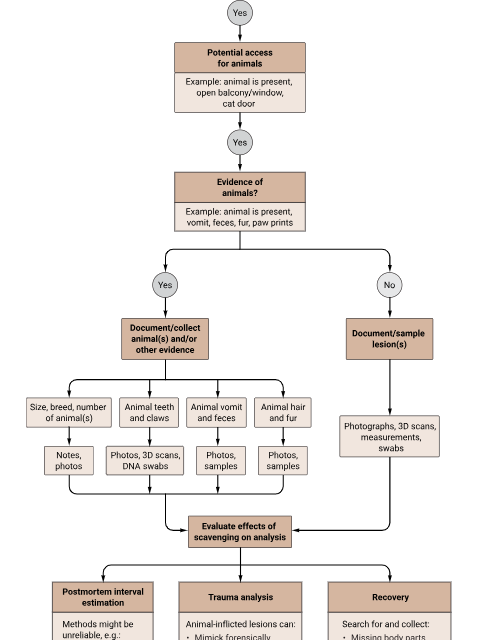

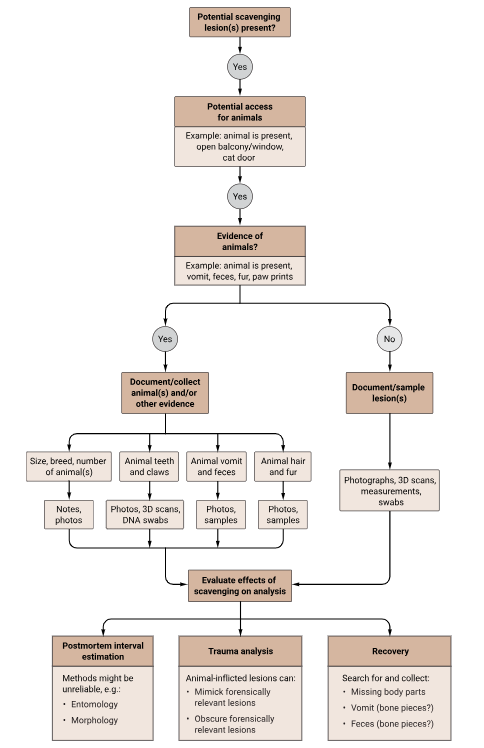

A new flowchart shows steps that investigators at a forensic scene should take when determining whether dogs or cats scavenged a human body.

The study suggests that investigators note the size, breed, and number of animals encountered, even if seemingly irrelevant to the case at hand. This information could prove valuable for future investigations where determining whether an animal affected a wound becomes crucial. The researchers have developed a flowchart for first responders at crime scenes, guiding them on collecting samples of fur and feces to consider when evaluating whether scavenging masked the cause of death.

Gabriel Fonseca, a forensic odontologist at the University of La Frontera, emphasizes the importance of trained first responders, noting that without them, the possibility of losing critical evidence becomes significant. The proposed habits in the study could aid in cases where pet scavenging obscures the cause of death for coroners.

The study’s findings underscore the need to consider overlooked information, says Fonseca, and the flowchart could prove beneficial in cases like a recent one in Chile where a woman’s face was eaten by her dog, masking injuries sustained during a robbery.

While the study is seen as an “interesting academic exercise,” according to Roger Byard, a forensic pathologist at the University of Adelaide, its relevance may vary depending on the circumstances. Byard suggests that in most cases, it may not matter whether postmortem injuries were caused by a dog or cat. However, Carolyn Rando believes that compiling such cases could reveal the frequency of pet scavenging, potentially showing trends like an increase during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For concerned pet owners, Rando suggests having someone regularly check on them and their animals, particularly if they live alone. The study raises awareness of a peculiar aspect of forensic investigations and prompts consideration of the impact of pet scavenging on understanding the circumstances of a person’s death.