Situation at a Glance

Description of the Situation

Patient samples were collected on 24 November 2023, at a hospital in the province, and, on 4 December 2023, were sent to the Reference Laboratory of the National Institute of Human Viral Diseases “Dr. Julio I. Maiztegui” (INEVH per its acronym in Spanish), which is part of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (ANLIS Malbrán). The samples tested positive on 19 December 2023 for the detection of specific neutralizing antibodies for the WEE virus. The samples also tested negative for other alphaviruses: Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) virus, Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis (VEE) virus, Una virus, Mayaro virus, and Chikungunya virus.

Epidemiology

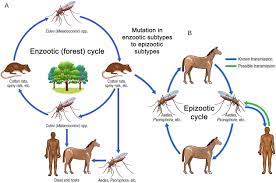

WEE is a rare mosquito-borne disease caused by a virus of the same name, which belongs to the genus Alphavirus of the Togaviridae family, to which the EEE and VEE viruses also belong. The main reservoir hosts of EEE and WEE viruses are passerine birds.2 In humans, the WEE virus can cause disease ranging from subclinical or moderate symptoms to severe forms of aseptic meningitis and encephalitis.

The virus has the potential to spread to other areas through the migration of infected birds or even through the movement of people and animals carrying the virus. Given that birds act as a reservoir, they can act as amplifying hosts for viral dissemination to other countries. At-risk groups include people who live, work, or participate in outdoor activities in endemic areas or where there are declared active disease outbreaks in animals.

In Argentina, between 25 November and 27 December of 2023, a total of 1182 outbreaks of WEE disease have been identified in equines in 12 provinces of the country: Buenos Aires (n = 717), Santa Fe (n = 149), Córdoba (n = 141), Entre Ríos (n = 69), Corrientes (n = 41), Chaco (n = 19), La Pampa (n = 18), Río Negro (n = 11), Formosa (n = 8), Santiago del Estero (n = 6), San Luis (n = 2), and Salta (n = 1).3

Public Health Response

Following the detection of the WEE virus in equines, the Ministry of Health activated a nationwide epidemiological alert, on 28 November 2023, to provide further information on the disease outbreaks in equines and to strengthen epidemiological surveillance of possible human cases. The epidemiological surveillance includes both passive and active case finding, the latter in areas with active disease outbreaks in animals, according to the case definitions established in the Circular for the epidemiological and laboratory surveillance, prevention and control of Western Equine Encephalitis in Argentina.4

Argentina’s national Ministry of Health is also working together with the National Food Safety and Quality Service (SENASA per its acronym in Spanish) and the Ministries of Health of the Province of Santa Fe and of other affected provinces, on the implementation of preventive measures, epidemiological surveillance and outbreak control actions.1

WHO Risk Assessment

The primary mode of WEE virus transmission is through the bites of infected mosquitoes, which act as vectors. The principal vector is Culex tarsalis; however, there are multiple vectors that contribute to transmission, including Aedes melanimon, Aedes dorsalis, and Aedes campestris. These vectors maintain the circulation of the virus in wild enzootic cycles where birds act as reservoirs of the virus. Humans and equines act as the final reservoirs of the virus, incapable of transmitting the virus to mosquitoes.5 People engaged in outside work or activities are at greater risk because of exposure to mosquitoes.

Outbreaks of WEE in humans generally present as isolated cases with moderate symptoms and most infections are asymptomatic. Neurological manifestations include meningitis, encephalitis, or myelitis. Similar to other arboviral encephalitis, the encephalitis caused by WEE is characterized by fever accompanied by altered mental status, seizures, or focal neurological signs including movement disorders.6 There is no specific antiviral treatment and patient management primarily involves supportive care measures.

WHO Advice

Below is a summary of the main recommendations for laboratory diagnosis in humans, surveillance, and prevention measures.

Laboratory diagnosis of WEE in humans

The diagnosis of WEE infection requires confirmation through laboratory techniques since the clinical presentation is not specific. These laboratory methods include virological (direct) diagnostic methods by nucleic acid amplification or potentially cell culture and serological (indirect) methods, aiming to detect antibodies produced against the virus. Generally, samples for diagnosis include serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF should only be collected in cases with neurological symptoms and by clinical indication. The diagnostic methods are described in more detail in the Laboratory Guidelines for the Detection and Diagnosis of Western Equine Encephalitis Virus Human Infection.7

Surveillance

In at-risk areas with reported active outbreaks in animals, strengthening surveillance is recommended with active human case finding for compatible neurological syndromes without any other defined diagnosis, taking into account the incubation period, geographic area, and environmental conditions.

Prevention Measures

Preventive actions, listed below, must be organized within the framework of One Health, considering the inter-institutional and comprehensive action between animal health, human health, and the environment.

Managing the environment

Considering the ecology and biology of the main vectors of the WEE virus, the main prevention measures recommended are modifying the environment and environmental management to reduce the number of mosquitoes and their contact with equines and humans. These measures include:

- Filling or draining water collections, ponds, or temporary flooding sites that may serve as sites of female oviposition and breeding sites for mosquito larvae.

- Elimination of weeds around premises to reduce mosquito resting and shelter sites.

- Protecting equines by sheltering them in stables with mosquito nets, particularly at times when mosquitoes are most active.

- Although the main vectors do not have indoor habits, it is advisable to protect homes with mosquito nets on doors and windows; in this way, other arboviruses are also prevented.

Vector Control

Vector control measures for the WEE virus should be considered within the Integrated Vector Management (IVM) framework. It is important to consider that the decision to carry out vector control activities with insecticides depends on entomological surveillance data and the variables that may increase in the risk of transmission, including insecticide resistance data. Insecticide spraying may be considered as an additional measure, where technically feasible, in areas of transmission where high mosquito populations are detected. The methodology should be established based on the ecology and behavior of local vectors.

Vaccination in equines

Vaccines are available for equines. It is advisable to seek high vaccination coverage among susceptible equines in areas considered at risk and to carry out annual vaccination boosters.

Personal Protective Measures

- Use of clothing that covers the legs and arms, especially in households where someone is ill.

- Use of repellents containing DEET, IR3535 or Icaridin, which may be applied to exposed skin or clothing, in strict accordance with the instructions on the product label.

- Use wire mesh/mosquito nets on doors and windows.

- Use of insecticide-treated or non-insecticide nets for daytime sleepers (e.g. pregnant women, infants, bedridden people, the elderly, and night shift workers).

- In outbreak situations, outdoor activities should be avoided during the period of greatest mosquito activity (dawn and dusk).

Further Information

- Argentina Ministry of Health. Press release. One human case of Western Equine Encephalitis was detected. Buenos Aires: MSAL; 2023. Available in Spanish from: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/se-detecto-un-caso-humano-de-encefalitis-equina-del-oeste

- Ministry of Health, Province of Santa Fe, Argentina. Press release. They highlight the role of health professionals in the diagnosis of the case of western equine encephalitis. Santa Fe 2023. Available in: https://www.santafe.gob.ar/noticias/noticia/279452/

- Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Epidemiological Alert: Risk to human health associated with infection with Western Equine Encephalitis in Equines, 20 December 2023. Washington, D.C.: PAHO/WHO; 2023. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/documentos/alerta-epidemiologica-riesgo-para-salud-humana-asociado-infeccion-por-virus-encefalitis

- World Organization for Animal Health. Global Animal Health Information System. Paris: WOAH; 2023 . Available from: https://wahis.woah.org/#/home

References:

- Argentina International Health Regulations (IHR) National Focal Point (NFP). Buenos Aires; 27 December 2023.Unpublished

- World Organization for Animal Health. Health Standards. Chapter 3.6.5. Equine encephalomyelitis (eastern, western, or Venezuelan). Paris: WOAH; 2021. Available from: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/fr/Health_standards/tahm/3.06.05_EEE_WEE_VEE.pdf

- National Food Safety and Quality Service of Argentina. National Directorate of Animal Health. DNSA Dashboard Western Equine Encephalomyelitis. Buenos Aires: SENASA; 2023 (accessed 27 December 2023). Available in Spanish from: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/senasa/encefalomielitis-equinas/tableros-dinamicos-informativos

- Ministry of Health of Argentina. Western Equine Encephalitis: Circular for epidemiological and laboratory surveillance, prevention and control. Buenos Aires: MSAL; 2023 Available in Spanish from: https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2023-12/circular-eeo_2023-12-08.pdf

- Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Guidance for Surveillance, Detection and Response for Equine Encephalitis 2014; 17. ISSN0101-6970. Washington, D.C.: PAHO/WHO; 2014. Available in Spanish from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/58684

- Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. American Public Health Association. Control of communicable diseases. An official report from the American Public Health Association ed. 21a. Page 34-39. ISBN-13: 978 0875533230.Washington, D.C.: PAHO/WHO; 2022

- Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Laboratory Guidelines for the Detection and Diagnosis of Western Equine Encephalitis Virus Human Infection. 20 December 2023. Washington, D.C.: PAHO/WHO; 2023. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/laboratory-guidelines-detection-and-diagnosis-western-equine-encephalitis-virus-human

Citable reference: World Health Organization (28 December 2023). Disease Outbreak News; Western equine encephalitis in Argentina. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON499