Situation at a glance

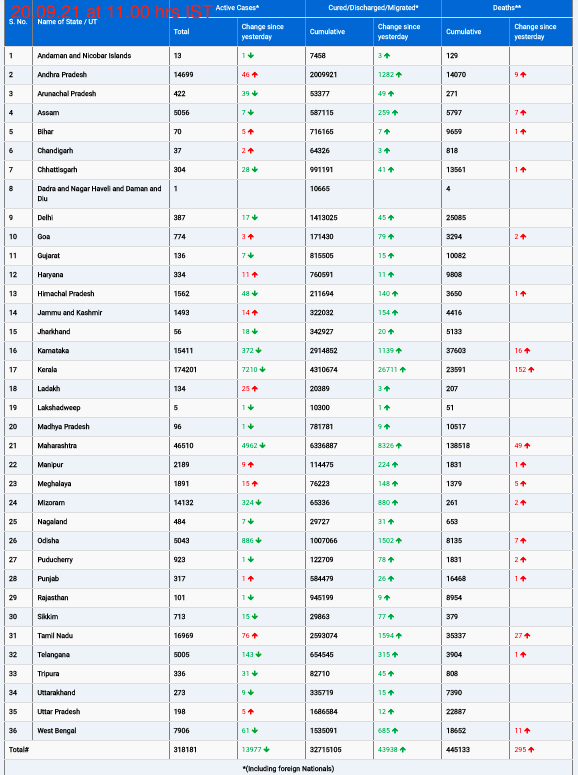

Since the beginning of 2023, dengue outbreaks of significant magnitude have been recorded in the WHO Region of the Americas, with close to three million suspected and confirmed cases of dengue reported so far this year, surpassing the 2.8 million cases of dengue registered for the entire year of 2022. Of the total number of dengue cases reported until 1 July 2023 (2 997 097 cases), 45% were laboratory confirmed, and 0.13% were classified as severe dengue. The highest number of dengue cases to date in 2023 are in Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia. Additionally, 1302 deaths were reported in the Region with a Case Fatality Rate (CFR) of 0.04%, in the same period.

As part of the implementation of the Integrated Management Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Arboviral Diseases (IMS-Arbovirus), WHO is actively working with the Member States to strengthen healthcare and surveillance capacity.

WHO has assessed the risk of dengue as high at the regional level due to the wide spread distribution of the Aedes spp. mosquitoes (especially Aedes aegypti), the continued risk of severe disease and death, and the expansion out of historical areas of transmission, where all the population, including risk groups and healthcare workers, may not be aware of warning signs.

WHO does not recommend any travel and/or trade restrictions for countries in the Americas experiencing the current dengue epidemics based on the currently available information.

Description of the situation

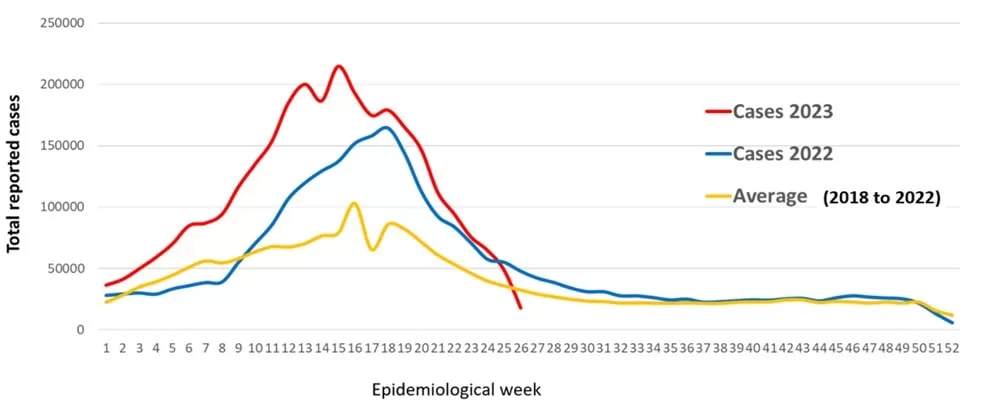

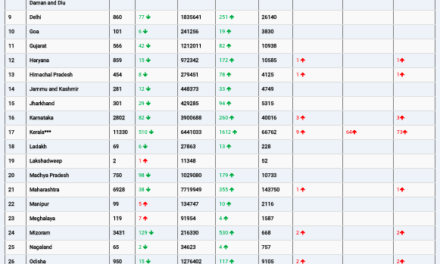

Dengue is the arbovirus that causes the highest number of cases in the Region of the Americas, with epidemics occurring cyclically every 3 to 5 years. During the first half of 2023, dengue outbreaks of significant magnitude were recorded in South America. Between epidemiological week (EW) 1 and EW 26 of 2023 (week ending on 01 July), a total of 2 997 097 cases of dengue were reported in the Region of the Americas, including 1302 deaths with a CFR of 0.04%, with a cumulative incidence rate of 305 cases per 100 000 population. Of the total number of dengue cases until EW 26 of 2023, 1 348 234 (45%) were laboratory confirmed, and 3907 (0.13%) were classified as severe dengue.1 The highest number of dengue cases was observed in Brazil, with 2 376 522 cases, followed by Peru with 188 326 cases, and Bolivia with 133 779 cases.

The highest cumulative incidence rates were observed in the following subregions: the Southern Cone2 with 862 cases per 100 000 inhabitants, the Andean Subregion3 with 268 cases per 100 000 inhabitants, and the Central American Isthmus and Mexico4 with 59 cases per 100 000 inhabitants.

The highest number of severe dengue cases was observed in the following countries: Brazil with 1249 cases, Peru with 701 cases, Colombia with 683 cases, Bolivia with 591 cases and Mexico with 141 cases.

All four dengue virus serotypes (DENV1, DENV2, DENV3, and DENV4) are present in the Region of the Americas. In 2023, up to EW 26 (ending on 1 July), simultaneous circulation of all four serotypes has been detected in Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Venezuela; while in Argentina, Panama, Peru, and Puerto Rico, DENV1, DENV2 and DENV3 serotypes circulate, and in Nicaragua the serotypes DENV1, DENV3 and DENV4.

In 2022, 2 811 433 dengue cases were reported in the Region of the Americas, the third highest year on record, only surpassed by 2016 and 2019. In 2019, the highest number of historical dengue cases was registered, with more than 3.1 million cases for the Region of the Americas, including 28 203 severe cases and 1823 deaths.

Between 12 June to 1 July 2023, some countries in the Southern Cone and the Andean subregion have been showing a decrease in the number of cases due to multiple factors, including, the implementation of control measures, and the change in temperature and climate, mainly in the Southern Cone. There is also a delay in the notification of data from some countries in Central America and the Caribbean. These have resulted in a decline in cases and the downward trend observed in the epidemiological curve below.

Figure 1. Number of dengue cases in 2022, 2023 (up to EW 26) and average of the last 5 years in the Region of the Americas

Source: Data entered into the Health Information Platform for the Americas (PLISA, PAHO/WHO) by the Ministries and Institutes of Health of the countries and territories of the Region. Available from: https://opendata.paho.org/en. Accessed July 11, 2023.

Figure 2. Suspected cases (A) and cumulative incidence per 100 0000 population(B) of dengue in the most affected countries** in the Region of the Americas, as of 01 July 2023

** Countries which reported 99% of cases in the Region of the Americas

Source: Data entered into the Health Information Platform for the Americas (PLISA, PAHO/WHO) by the Ministries and Institutes of Health of the countries and territories of the Region. Accessed July 11, 2023

Figure 3. Deaths(A) and CFR(B) from dengue in the Region of the Americas, as of EW 26, 2023

Source: Data entered into the Health Information Platform for the Americas (PLISA, PAHO/WHO) by the Ministries and Institutes of Health of the countries and territories of the Region.

Overview by selected countries

Although dengue is endemic in most countries of South America, Central America, and the Caribbean, during the current season, an increase in dengue cases has been observed at levels above the average number of cases recorded in the last five years and beyond historical areas of transmission. Below is a summary of the epidemiological situation of dengue in most affected countries5 in the Region of the Americas reported to PAHO/WHO.

Argentina6

According to the Argentina IHR National Focal Point, up to EW 26 of 2023 (week ending on 01 July), 126 431 cases of dengue were reported, of which 118 089 were autochthonous, 1398 were imported, and 6944 are under investigation. Fifty-three percent of the cases were laboratory-confirmed and 304 (0.24%) were classified as severe dengue. A total of 65 deaths were reported during this period with a CFR of 0.05%. Compared to the last epidemiological outbreak of dengue recorded in the country in the 2019/2020 season (59 264 cases year 2020), there is a 47% increase in the number of cases in the 2022/2023 period (126 431 cases year 2023).

Brazil

In 2023 up to EW 26, of the 2 376 522 reported dengue cases, 1 051 773 (44.2%) were laboratory confirmed, and 1 249 (0.05%) were classified as severe dengue. The cases registered up to EW 26 of 2023 show an increase of 13% compared to the same period of 2022 and 73% compared to the average of the last five years. In the same period, a total of 769 deaths were reported with CFR of 0.03%.

Bolivia

In 2023 up to EW 25, of the 133 779 reported dengue cases, 22 761 (17%) were laboratory confirmed, and 591 (0.44%) were classified as severe dengue. The cases registered to EW 25 of 2023 are 16 times higher than those reported in the same period of 2022 and five times higher compared to the average of the last five years. In the same period, 77 deaths were reported with CFR of 0.06%.

Colombia

In 2023 up to EW 25, of the 50 818 reported dengue cases, 25 958 (51%) were laboratory confirmed, and 683 (1.34%) were classified as severe dengue. The cases registered in EW 25 of 2023 are 66% higher than those reported in the same period of 2022 and 47% higher compared to the average of the last five years. In the same period, 29 deaths were reported with CFR of 0.06%.

Costa Rica

In 2023, up to EW 25, of the 2712 reported dengue cases, 254 (9.3%) were laboratory confirmed, and there were no cases of severe dengue. The cases registered up to EW 25 of 2023 are 16% higher compared to the same period of 2022, and 19% higher compared to the average of the last five years. In the same period, no deaths were reported.

Guatemala

In 2023, up to EW 24, of the 4529 reported dengue cases, 699 (15%) were laboratory confirmed, and six (0.13%) were classified as severe dengue. The cases registered up to EW 24 of 2023 are 80% higher compared to the same period of 2022, and 45% higher compared to the average of the last five years. In the same period, five deaths were reported with CFR of 0.11%.

Mexico7

According to the Mexico IHR National Focal Point, up to EW 26 of 2023, of the 31 549 reported dengue cases, 4400 (14%) were laboratory confirmed, and 141 (2%) were classified as severe dengue. The cases registered up to EW 26 of 2023 are 2.5 times higher compared to the same period in 2022 and 58% higher compared to the average of the last five years. In the same period, five deaths were reported with CFR of 0.02%.

Nicaragua

In 2023, up to EW 25, of the 56 780 reported suspected dengue cases, 1016 (1.8%) were laboratory confirmed, and 10 (0.02%) were classified as severe dengue. The cases registered up to EW 25 of 2023 are 2.7 times higher compared to the same period in 2022 and 2.1 times higher compared to the average of the last five years. In the same period, one death was reported with CFR of 0.002%.

Panama8

In 2023, up to EW 24, of the 3176 reported dengue cases, 2161 (68%) were laboratory confirmed, and seven (0.22%) were classified as severe dengue. The cases registered up to EW 24 of 2023 are 54% higher compared to the same period of 2022, and 63% higher compared to the average of the last five years. In the same period, no deaths were reported.

Peru9

In 2023 up to EW 26, of the 188 326 reported dengue cases, 105 215 (55.9%) were laboratory confirmed, and 701 (0.37%) were classified as severe dengue. The cases registered up to EW 26 of 2023 are 3.1 times higher than those reported in the same period of 2022. In the same period, a total of 325 deaths were reported between suspected and confirmed cases, with CFR of 0.17%.

Epidemiology of the disease

Dengue is a viral infection that spreads from mosquitoes to people. It is more common in tropical and subtropical climates. Most people who get dengue won’t have symptoms. But for those that do, the most common symptoms are high fever, headache, body aches, nausea and rash. Most people will get better in 1–2 weeks, however, some people develop severe dengue which includes shock or respiratory distress due to plasma leakage, severe bleeding, organ impairment, and death.

In severe cases, dengue can be fatal. The risk of dengue can be avoided by avoiding mosquito bites especially during the day. There is currently no specific treatment for dengue, therefore, case management focuses on managing pain symptoms with Acetaminophen. Some of the severe cases are secondary infections (people getting infected for a second time with another serotype).

The incidence of dengue has grown dramatically around the world in recent decades, with cases reported to WHO increasing from 505 430 cases in 2000 to 5.2 million in 2019 globally. A vast majority of cases are asymptomatic or mild and self-managed, and hence the actual numbers of dengue cases are under-reported. Many cases are also misdiagnosed as other febrile illnesses.

The disease is now endemic in more than 100 countries in the WHO Regions of Africa, the Americas, the Eastern Mediterranean, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific. The Americas, South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions are the most seriously affected, with Asia representing around 70% of the global disease burden.

The largest number of dengue cases ever reported globally was in 2019. All regions were affected, and dengue transmission was recorded in Afghanistan for the first time. The American Region reported 3.1 million cases, with more than 25 000 classified as severe. A high number of cases were reported in Bangladesh (101 000), Malaysia (131 000) Philippines (420 000), and Vietnam (320 000).

Public health response

Ministry of Health (MoH) response:

- Regular meetings with national and subnational health authorities. Some countries have implemented Emergency Center Operations (EOC) for a suitable outbreak response.

- Strengthened surveillance activities for early detection of cases.

- Strengthened vector-control activities in affected areas.

- Strengthening of the laboratory network.

- Trained healthcare professionals in the detection of warning signals of severe dengue.

- Facilitated awareness raising among health workers (by sharing factsheets and surveillance tools) and to the local population using risk communication messages.

- Some countries have national networks of clinical experts in arboviral diseases under the direction of the Ministries of Health in each country, which are responsible for conducting clinical training at the local level.

WHO response:

- As part of the implementation of the Integrated Management Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Arboviral Diseases (IMS-Arbovirus), WHO is actively working with the Member States so that they can strengthen healthcare and surveillance capacity.

- WHO has been supporting Member States in preparedness and response to possible outbreaks, including the organization of health services.

- WHO is supporting the implementation of effective integrated vector surveillance and control by Member States through publishing guidelines and the provision of epidemiological surveillance materials and technical assistance to national authorities.

- WHO is supporting the increase of laboratory-capacity to enable timely and accurate diagnosis and case detection throughout the region.

- WHO is supporting health care workers capacity building through case management recommendations and clinical care training.

- WHO experts are being deployed to countries that are experiencing high-magnitude outbreaks.

- In 2020, WHO began a collaboration with the Andean Health Organization-Hipólito Unanue Agreement (ORAS-CONHU) to strengthen national technical capacities for the prevention and control of arboviral diseases in Bolivia, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. This collaboration falls under the framework of the Integrated Management Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Arboviral Diseases, approved by WHO.

- Virtual cooperation spaces (VCS) have been created as an effort of collaborative surveillance between WHO and the Member States that allow the automated generation of different epidemiological analyses, situation rooms, and epidemiological bulletins, strengthening the epidemiological surveillance of dengue and other arboviruses.

- WHO also provides advice on risk assessment and risk communication.

WHO risk assessment

Dengue is a mosquito – borne viral disease (arbovirus) that has the potential to cause serious public health impact. The virus that causes this infection has been circulating in the region of the Americas for decades10 due to the widespread distribution of the Aedes spp. mosquitoes (mainly Aedes aegypti), with epidemics occurring cyclically every 3 to 5 years. Several dengue outbreaks have been documented previously in the Region.

This arbovirus can be carried by infected travellers (imported cases) and may establish new areas of local transmission in the presence of vectors and a susceptible population. As they are arboviruses, all populations living in areas with the presence of Aedes aegypti are at risk, however, their impact largely affects the most vulnerable people, in which the arboviral disease programs do not have enough resources to respond to outbreaks.

The consequences of the current high transmission scenario depend on several factors, including the current capacities for a coordinated public health response and clinical management, the early start of the arbovirus season in the southern hemisphere, high mosquito densities and the possible impact of climate change and El Nino phenomenon in the southern hemisphere, lack of vector surveillance and control activities during the COVID-19 pandemic and high proportion of the susceptible population for arboviruses in the region. The current high transmission scenario for dengue occurs in the context of other ongoing outbreaks and emergencies. The synergic effects of concurrent emergencies may hinder the health system’s capacity to respond to an epidemic of arboviral diseases and therefore affect disease control and proper clinical management, including, but not limited to (i) misdiagnosis, given that dengue symptoms may be non-specific and resemble other infections, including chikungunya, Zika and measles, potentially leading to inadequate case management; (ii) overwhelmed healthcare facilities in some areas given high caseload, as well as other concurrent outbreaks of other communicable diseases; and (iii) the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the decrease of available resources to arboviral disease programs and the need for capacity building and training of vector-control and healthcare workers, as well as maintenance and procurement of equipment and insecticides to perform vector control activities.

Dengue is endemic in most countries of South America. However, during the seasonal period in the first half of 2023, where dengue outbreaks have been detected, there has been an increase in the number of cases at levels above the average number of cases recorded in the last five years and the expansion of dengue out of historical areas of transmission.

Aedes spp. mosquitoes are widely distributed in the Region of the Americas, therefore, dengue international spread is likely. Additionally, it is expected that in the second half of 2023, some countries in the Region, especially in Central America and the Caribbean, will have an increase in rainfall, which, depending on its magnitude and impact on dengue-endemic areas, could increase the incidence of the disease and constitute an additional burden of arboviral diseases for health systems in affected areas.

The risk at the regional level is assessed as high due to the widely spread distribution of the vector (especially Aedes aegypti), the continued risk of severe disease and even death, and the expansion out of historical areas of transmission, where all the population, including risk groups and healthcare workers, may not be aware of warning signs.

Information on the circulating dengue virus serotype is limited. It is expected that a large proportion of the population in these areas is naïve to the current virus circulating, which may lead to outbreaks. Moreover, people in these areas may not be aware of warning signs, and the population might delay seeking health care.

In some areas, there is a lack of medical facilities with limited geographical access, making it difficult for people to access basic health care. Especially in these areas, people tend to self-medicate, and in dengue cases ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated because they can aggravate gastritis or bleeding and lead to increased mortality risk.

Other challenges reported by Member States in the Region include but are not limited to stockouts of several essential supplies for prevention and control, lack of reagents and consumables for laboratory diagnosis, and the need for re-training field teams and health workers. In addition, higher transmission rates are expected in the following months due to favourable weather conditions to vector activity in the second half of the year in Central America and the northern hemisphere.

WHO advice

Dengue is caused by the dengue virus (DENV), an RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae. There are four distinct but closely related serotypes of the virus (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4) – recovery from infection provides lifelong immunity against that serotype. Although most cases of dengue are mild, the sequential infection by more than one serotype increases the risk of developing severe dengue, which includes shock or respiratory distress due to plasma leakage, severe bleeding, organ impairment, and death.

Prevention efforts are highly focused on the surveillance and control of Aedes spp. mosquitoes (the most competent vector in the region). Since vector surveillance and control may be difficult to sustain, especially in areas where DENV is endemic year-round, early detection of severe disease progression and access to proper medical attention is key to lowering severe case rates and, therefore, case fatality rates. Personal protection and source reduction measures should be maintained by communities both at places of work or study and at homes. No specific antiviral treatment exists for chikungunya and dengue. Clinical management is based on supportive care, including fluids and antipyretics; recovery can provide immunity (for that specific serotype in dengue cases). As symptoms of these arboviruses may overlap, clinical-epidemiological diagnostic may be challenging, and there is cross-reactivity of the immunoglobulin M and G antibodies (IgM and IgG) of dengue and Zika viruses, hindering accurate diagnosis, which can lead to inadequate case management, and compromising efficient epidemiological surveillance. The reason why molecular diagnosis with RT-PCR is recommended.

It is very important that the Member States in the Americas are extremely vigilant and prepared to intensify actions to prevent, early detect, diagnose, and control arboviruses, including training and alerting healthcare workers on the detection of cases and potential complications of these diseases, identification of risk groups for severe disease, appropriate clinical management and follow up of cases to prevent future deaths. In the second half of 2023, an increase in dengue cases is expected. Targeted integrated vector surveillance, monitoring insecticide resistance in dengue vector and control measures are helpful in reducing transmission rates. As a general precaution, WHO recommends avoidance of mosquito bites, including the use of repellents. The highest risk for transmission of dengue is during the day and early evening.

WHO reiterates to all Member States the importance of strengthening: 1) their laboratory capacity to recognize and confirm the cases timely; 2) their healthcare capacity to rapidly detect and manage cases, and 3) their surveillance capacity to rapidly detect trends on the incidence and implement control measures. It is relevant to maintain close monitoring of the situation in the region with active cross-border coordination and information sharing because of the possibility of cases in neighbouring countries.

WHO does not recommend any travel and/or trade restrictions for countries in the Americas experiencing the current dengue epidemics based on the currently available information.

Further information

- Dengue and severe dengue fact sheet: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue

- Pan-American Health Organization/ World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). Health Information Platform for the Americas (PLISA as per its acronym in Spanish). Washington, DC: PAHO; 2023. accessed on 11 July 2023. Available from: https://bit.ly/314Snw4(link is external)

- PAHO/WHO. Epidemiological Update: Dengue in the Region of the Americas. 5 July 2023. Washington, D.C. PAHO/WHO; 2023.

- PAHO/WHO. Guidelines for the Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. Available from: https://bit.ly/3SB0nkn

- PAHO/WHO. Methodology for Evaluating National Arboviral Disease Prevention and Control Strategies in the Americas. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2021. Available from: https://bit.ly/3JoQt2t

- PAHO/WHO. Dengue Outbreak Early Warning and Response System: Operational Guide Based on Online Dashboard. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2021. Available in Spanish from: https://bit.ly/3H1Oz3D(link is external)

- PAHO/WHO. Integrated Management Strategy for Arboviral Disease Prevention and Control in the Americas. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2020. Available from: https://bit.ly/3ylDEj

- PAHO Risk evaluation on chikungunya – Implications for the Region of the Americas. 9 March 2023. Available at: https://bit.ly/3yp6ajQ(link is external)

- PAHO/WHO. Epidemiological Alert: Increase in cases and deaths from chikungunya in the Region of the Americas. 8 March 2023, Washington, D.C: PAHO/WHO; 2023. Available from: https://bit.ly/426w5KS(link is external)

- PAHO/WHO. Epidemiological Alert: Chikungunya increase in the Region of the Americas. 13 February 2023, Washington, D.C. PAHO / WHO. 2023. Available from: https://bit.ly/3YxCuvw(link is external)

- PAHO/WHO. Epidemiological Update: Dengue, chikungunya and Zika. 25 January 2023, Washington, D.C. PAHO / WHO. 2023. Available from: https://bit.ly/3ZDFlEe(link is external)

- PAHO/WHO. Topics – Dengue. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2023. Available from: https://bit.ly/41vvIZT(link is external)

- PAHO/WHO. Technical document for the implementation of interventions based on generic operational scenarios for Aedes aegypti control. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2019. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/51652/9789275121108_eng.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y(link is external)

- PAHO/WHO. Manual for Indoor Residual Spraying in Urban Areas for Aedes aegypti Control. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2019. Available from: https://bit.ly/3NJnlnx(link is external)

- PAHO/WHO. Evaluation of Innovative Strategies for Aedes aegypti Control: Challenges for their Introduction and Impact Assessment. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2019. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51375(link is external)

- WHO. Dengue factsheet. Geneva: WHO 2023. Available from: https://bit.ly/2CpkP0Y(link is external)

- Roca, Y., Baronti, C., Revollo, R. J., Cook, S., Loayza, R., Ninove, L., Fernandez, R. T., Flores, J. V., Herve, J. P., & de Lamballerie, X. (2009). Molecular epidemiological analysis of dengue fever in Bolivia from 1998 to 2008. Vector borne and zoonotic diseases (Larchmont, N.Y.), 9(3), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2008.0187(link is external)

- Brathwaite Dick, O., San Martín, J. L., Montoya, R. H., del Diego, J., Zambrano, B., & Dayan, G. H. (2012). The history of dengue outbreaks in the Americas. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 87(4), 584–593. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0770

[1] Argentina, Brasil, Chile Paraguay y Uruguay.

[2] Bolivia,Colombia, Ecuador,Perú y Venezuela.

[3] Belice, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, México, Nicaragua y Panamá.

[4] Data entered into the Health Information Platform for the Americas (PLISA, PAHO/WHO) by the Ministries and Institutes of Health of the countries and territories of the Region. Available from: https://opendata.paho.org/en. Accessed 11 July 2023.

[5] Countries which reported 99% of cases in the Region of the Americas

[6] Information provided by the Argentina IHR National Focal Point (NFP).

[7] Information provided by the Mexico IHR NFP.

[8] Information provided by the Panama IHR National Focal Point (NFP).

[9] Information provided by the Peru IHR National Focal Point (NFP).

[10] Dengue incidence has increased in the Americas over the past four decades, from 1.5 million cumulative cases in the 1980s to 16.2 million in the decade 2010-2019.

Citable reference: World Health Organization (19 July 2023). Disease Outbreak News; Dengue in the Region of the Americas. Available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON475