AUSTIN, Texas — Self-treatment of migraines using cannabis can be effective but comes at risk of significant side effects, according to results from a randomized, controlled trial of cannabis products in migraine. The study also suggests that typical recreational doses may be higher than needed, and that products with a mixture of THC and CBD might limit adverse effects, according to lead author Nathaniel Schuster, MD.

“Patients are using cannabis on their own, treating themselves without us having known whether this is effective in a placebo-controlled study. Knowing that there’s a lot of interest in THC and CBD, [it would be useful to know] whether one or both might be effective, as well as a mix,” said Dr. Schuster in an interview. He presented the results at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Dr. Schuster and colleagues tested a cannabis product with 6% THC based on prior studies showing efficacy of that concentration for other pain conditions, according to Dr. Schuster, who is an associate professor and associate clinical director at the University of California, San Diego, center for pain medicine. He added that the study is the first randomized, controlled trial of cannabis in migraine patients that he is aware of. “It’s just hard to do this research. It’s very regulated. We had to go through a lot of government approvals to do this,” he said.

The study produced a key message. “I think one of the really important things for patients to take from this is that recreational doses are probably not necessary. The doses that we studied are lower than people use recreationally. Patients who are self-treating on their own right now are probably using higher doses than they need for the purpose of treating migraine,” said Dr. Schuster.

He also pointed out that the results offer potential insight into reducing side effects. “If [patients] are using THC only, they can hopefully have less of the side effects and tolerate it better by using a THC-CBD mix,” said Dr. Schuster.

Four therapies tested

Participants in the study could self-treat up to four migraine attacks. They were instructed to treat each migraine with one of four therapies, which were provided in a randomized, double-blind order: These included a 6% THC formulation; a mix of THC (6%) and CBD (11%); a CBD 11% formulation; and placebo cannabis with THC and CBD removed by alcohol extraction. Participants filled out a questionnaire 2 hours after treatment, and were then allowed to use rescue treatments if needed, but not additional cannabis. The age range was from 21 to 65, and inclusion criteria included 2-23 migraine days per month. Exclusion criteria included a positive urine test for THC, barbiturates, opioids, oxycodone, or methadone prior to enrollment.

The study included 73 patients who treated a migraine during the study period. There were 247 migraine attacks treated. Among participants, the median age was 41, 82.6% were female and 17.4% were male, and the median body mass index was 26.0 kg/m 2. Participants experienced a median of 15 headache days per month and 6 migraine days per month, and 27.2% had chronic migraine.

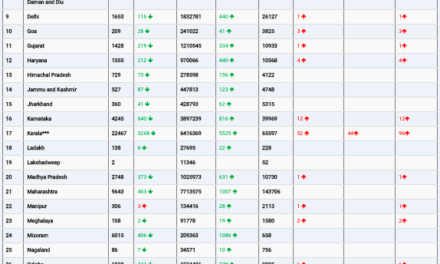

At 2 hours, pain relief occurred in 48.3% of placebo treatments, 54.4% of the CBD treatments, 70.5% of the THC treatments ( P = .007 versus placebo), and 69.0% of the THC/CBD treatments ( P = .014 versus placebo). At 2 hours, pain freedom occurred in 15.5% of the placebo treatments, 24.6% of the CBD treatments, 29.5% of the THC treatments, and 36.2% of the THC/CBD treatments ( P = .010 versus placebo). At 2 hours, freedom from most bothersome symptoms (MBS) occurred in 36.2% of the placebo treatments, 43.9% of the CBD treatments, 49.2% of the THC treatments, and 62.1% of the THC/CBD treatments (P = .004 versus placebo).

To achieve at least a 20% improvement in pain relief, compared with placebo, the number needed to treat (NNT) with THC/CBD was five. For at least a 20% improvement in pain freedom, the NNT was five, and for a 20% improvement in freedom from most bothersome symptoms, the NNT was four.

Treatment with THC was associated with the highest frequency of any adverse event (31.0%), followed by CBD and THC/CBD (19.6% each), and placebo (5.0%). At 2 hours, 18.0% of the THC treatments had an adverse event, compared with 7.0% of the CBD treatments, 6.9% of the THC/CBD treatments, and 5.2% of placebo treatments.

The number needed to treat of five for pain relief was encouraging, according to Dr. Schuster. “It’s better than some other things, but at the expense of side effects. The side effects that we see are certainly higher with cannabis than it is with other migraine treatments that patients certainly should be using beforehand. There’s also a risk of addiction, which is a concern,” said Dr. Schuster.

Useful data but questions remain

Having a clinical trial will be useful for physicians, said Ali Ezzati, MD, who attended the session. “I think it was an impressive study. Obviously, there are some challenges with cannabis studies in the medical world because of the stigma that comes with it and also the possibility of inducing addiction [and] promoting that to patients. But at the end of the day, it’s very, very common for our patients to ask us about cannabinoid use, and we really don’t have data on it. I’m glad that there are people who are running these studies so we will be able at least to answer our patients,” said Dr. Ezzati, who is an associate professor of neurology at University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Ezzati also noted that clinical trials have investigated cannabinoid use for other types of pain, such as arthritic or generalized pain. Although he said that there are some clinical similarities between other types of pain and migraine, the pathophysiology appears to be unique, which means that more work needs to be done. “It will probably take 5 or 10 years to have sufficient data to give patients a direct path for using (cannabinoids),” said Dr. Ezzati.

The study was funded by the Migraine Research Foundation. Dr. Schuster has consulted with Schedule 1 Therapeutics and Vectura Fertin. Dr. Ezzati has no relevant financial disclosures.

This article originally appeared on MDedge.com, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

By Jim Kling Medscape