Situation at a glance

In Mozambique, an outbreak of cholera has been growing exponentially since December 2022 with geographic spread to new districts. Heavy rainfall in the first weeks of February threatens to further worsen the situation.

The first case of cholera in the current outbreak was reported to the Ministry of Health and WHO from Lago district in Niassa province on 14 September 2022. As of 19 February 2023, a cumulative total of 5237 suspected cases and 37 deaths (Case Fatality Ratio (CFR) 0.7%) have been reported in 29 districts from six out of 11 provinces in the country. Of the at least 182 cases tested, 99 cases (54%) were laboratory confirmed for cholera by culture.

All six provinces currently affected by cholera are flood-prone areas. As the rainy season continues, it is anticipated that more districts will be affected. With this outbreak, cholera has affected many districts that had not reported any cases in over five years and where, as a result, the response capacity is limited.

In addition, there is inadequate access to sources of safe drinking water for the population that is already challenged with poor hygiene and sanitation.

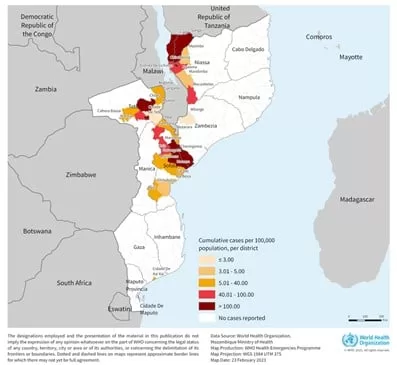

Mozambique is one of many countries in the region facing a cholera outbreak at the moment. Notably, neighbouring Malawi is facing the deadliest cholera outbreak in its history. Considering the frequency of cross-border movement and the history of cross-border spread of cholera during this outbreak, WHO considers the risk of further disease spread as very high at the national and regional levels.

Description of the outbreak

The first case of cholera in the current outbreak was reported to the Ministry of Health and WHO from Lago district in Niassa province on 14 September 2022.

As of 19 February 2023, a cumulative total of 5237 suspected cases and 37 deaths (CFR 0.7%) have been reported in 29 districts from six of 11 provinces in the country. Of at least 182 cases tested, 99 cases (54%) were laboratory confirmed for cholera due to the identification of Vibrio cholerae Ogawa by culture. As of 19 February, eight districts (Chimbonila, Lago, Lichinga, Mandimba, Mecanhelas, Muembe, Ngauma and Sanga) of Niassa province (north of the country) reported 2525 cases and 16 deaths (CFR 0.6 %). In the central region of the country, nine districts (Beira, Buzi, Caia, Cheringoma, Chibabava, Gorongoza, Maringue, Marromeu, Muanza) of Sofala province reported 1354 cases and three deaths (CFR 0.2 %). Nine districts (Angonia, Cahora Bassa, Chiuta, Doa, Marara, Moatize, Mutarara, Tete, Tsangano) from Tete province, reported 1271 cases with 12 deaths (CFR 0.9%) since December 2022. Zambezia province (Milange district) bordering Malawi reported 14 cases. In the southern region of the country, one district (Xai-Xai) in Gaza province, reported 42 cases and four deaths (CFR 9.5%). In addition, one district (Tambara) in Manica province, reported 34 cases and two deaths (CFR 5.9%).

Additionally, four districts from three provinces (Tete – two, Zambezia – one, and Cabo-Delgado – one) have reported cases of Acute Watery Diarrhoea (AWD) that were positive for cholera by Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) with culture results pending. Notably, in the last 30 days the districts reporting cholera and AWD are increasing, with three new provinces reporting confirmed cholera.

Prior to the current outbreak, there were cholera outbreaks in eight districts in three provinces during the first half of 2022, which were declared over. The current outbreak of cholera in Mozambique covers a wider geographic area and has a higher CFR compared with the previous outbreak. Moreover, most of the affected districts, especially in Niassa province, had not reported cholera cases for more than five years and many of the health professionals do not have experience in responding to a cholera outbreak. Weak surveillance with late reporting, inadequate WASH conditions (lack of access to safe drinking water, poor sanitation and hygiene practices), a weak health system and exhausted workforce responding to multiple emergencies pose a threat to continued disease progression, as do the ongoing heavy rains of the season.

Figure 1. Cholera cases reported by week and province in Mozambique from 14 September 2022 to 19 February 2023*  * The 14 cases from Zambezia district are not indicated figure 1

* The 14 cases from Zambezia district are not indicated figure 1

Figure 2. The cumulative number of cholera cases per 100 000 population in Mozambique by reporting districts as of 19 February 2023

Epidemiology of cholera

Cholera is an acute enteric infection caused by ingesting the bacteria Vibrio cholerae present in contaminated water or food. It is mainly linked to insufficient access to safe drinking water and inadequate sanitation. It is an extremely virulent disease that can cause severe acute watery diarrhoea resulting in high morbidity and mortality, and can spread rapidly, depending on the frequency of exposure, the exposed population and the setting. Cholera affects both children and adults and can be fatal if untreated.

The incubation period is between 12 hours and five days after ingestion of contaminated food or water. Most people infected with V. cholerae do not develop any symptoms, although the bacteria are present in their faeces for 1-10 days after infection and are shed back into the environment, potentially infecting other people. The majority of people who develop symptoms have mild or moderate symptoms, while a minority develop acute watery diarrhoea and vomiting with severe dehydration. Cholera is an easily treatable disease. Most people can be treated successfully through prompt administration of Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS).

The consequences of a humanitarian crisis or disasters like flooding– such as disruption of water and sanitation systems, or the displacement of populations towards inadequate and overcrowded camps – can increase the risk of cholera transmission, should the bacteria be present or introduced.

A multisectoral approach including a combination of surveillance, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), social mobilization, treatment, and oral cholera vaccines is essential to control cholera outbreaks and to reduce deaths.

Public health response

Since the outbreak was declared in September 2022, a national cholera task force was activated and WHO, along with other partners, is supporting the response. Specific actions undertaken include:

Coordination:

- The national cholera task force was activated with the involvement of the different working groups and cooperation partners, and weekly meetings are held.

- Health Cluster meetings on the cholera outbreak to discuss partner support are ongoing. Health and WASH clusters are maintaining a 4W (Who, What, Where and When) matrix to map partners interventions, gaps, needs and response for each affected district.

- Multisectoral coordination meetings are held weekly at district level and daily at provincial level. Cross-border coordination mechanisms are in place. Three cross-border meetings with Malawi have so far been conducted.

Epidemiological surveillance and laboratory:

- Case detection continues at the community and health facility level. The National Rapid Response Teams (RRT) was established in each district continue to investigate the cases. Data collection is being done daily and a daily bulletin is being produced.

- Rapid test kits were allocated to priority districts. Testing of suspected cases is being carried out with support from the National Institute of Health.

Case management:

- RRT are available and deployed in affected states.

- Training in case management was conducted for all 16 districts in Niassa province.

- WHO has provided six tents, cholera kits (central, periphery, community), Intravenous (IV) cannulas, cholera RDT kits and other consumables.

- Cholera treatment centers and cholera treatment units were set up in affected districts.

Infection Prevention and Control (IPC)/Water, Hygiene and Sanitation (WASH):

- Additional surge staff deployment to strengthen surveillance, Infection Prevention and Control (IPC), case management and logistics is underway.

- Advocacy was conducted with the other partners supporting WASH functions. UNICEF and MSF have allocated water purifiers (CERTEZA), chlorine and bleach.

- Support visits on IPC and WASH in cholera treatment centres have been conducted.

Risk communication and community engagement:

- Messages on cholera prevention and control have been translated into local languages and distributed door-to-door and in market places.

- Risk communication and community mobilization sessions are taking place in the communities.

Vaccination:

- A request for approximately 700 000 doses of Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV) was approved by the International Coordinating Group (ICG) on Vaccine Provision and a vaccination campaign in affected districts in Gaza, Niassa, Sofala and Zambezia provinces is in preparation and will start on 27 February 2023.

WHO risk assessment

Cholera is endemic in Mozambique and cholera outbreaks have been reported in the country every year during the hot and rainy season (October to April), mainly from Nampula, Cabo Delgado, Sofala and Tete provinces. However, the current outbreak has greater geographical extent than outbreaks reported in 2019-2022, when no more than three provinces were affected during the year.

The first cholera case of the current outbreak was reported from Lago district on 14 September 2022, Niassa province, located in the northern region of the country, which shares a border with Malawi and Tanzania.

All six provinces currently affected by cholera are located in the Zambezia Valley, which is a flood-prone area. As the rainy season continues, it is anticipated that more districts will be affected. The rainy season lasts until March-April, usually with a peak of rainfall recorded in January and early February. Heavy rainfall has already been reported in seven out of eleven provinces in the first weeks of February (31 January to 9 February), with flooding in Maputo province leading to displacement and disruption of the water supply system. There is inadequate access to safe drinking water sources for the population that is already challenged with poor hygiene and sanitation and the current rainy season could contribute to sustained disease transmission.

Several affected provinces, such as Niassa, Tete and Zambezia, are bordering Malawi, which is currently facing its deadliest cholera outbreak in history. The borders with Malawi are porous with frequent movement across the border between the two countries.

On 26 January 2023, Zambia notified WHO of a cholera outbreak in its Eastern Province bordering Malawi and Mozambique, where one of the two index cases had just returned from Mozambique. There remains a high risk of spread to other countries in the region, including Tanzania and Zimbabwe and further to South Africa. Considering the history of cross-border spread of cholera during this outbreak, the risk of further disease spread is therefore considered very high at the national and regional levels.

WHO advice

A multi-pronged approach is essential to combat cholera and reduce mortality. The measures used combine surveillance, improvement of water supply, sanitation and hygiene, risk communication and community engagement, treatment of the disease and use of oral cholera vaccines. Countries affected by cholera are advised to strengthen disease surveillance and national preparedness to rapidly detect and respond to possible outbreaks.

WHO recommends improving access to proper and timely case management of cholera cases, improving access to safe drinking water and sanitation infrastructure, as well as improving infection prevention and control in healthcare facilities.

Promotion of preventive hygiene practices and food safety in affected communities are the most effective means of controlling cholera. Targeted public health risk communication messages are a key element for a successful response. Promoting hand hygiene, use of toilets and food safety are effective means of preventing cholera. Serious symptoms and deaths can be prevented by ensuring communities understand the importance of ensuring people with cholera symptoms are well hydrated using oral rehydration solution and rapidly seeking care. Socio-behavioural data should be collected to understand community knowledge, risk perception, levels of trust, rumours and misinformation, behaviours, attitudes and practices; this data should be used to drive risk communication and community engagement activities and to inform those of other response pillars. Feedback systems should be established to enable those affected by the outbreak and response efforts to have two way communication with responders, with regular responses to their feedback to maintain trust.

Measures aimed at improving environmental conditions include applying long-term sustainable solutions for safe water supply, sanitation and hygiene in cholera-prone areas. Communities should be proactively engaged in the planning and implementation of these solutions. In addition to cholera, these interventions can also prevent a wide range of other water-borne diseases and contribute to achieving goals in education and the fight against poverty and malnutrition. Solutions for safe water supply, sanitation and hygiene related to cholera are in line with the Sustainable Development Goals.

Rapid access to treatment is essential during a cholera outbreak. Oral rehydration solution should be available in communities and not just in larger health centers that can offer intravenous infusions and management at any time. Where these are not easily available, communities should be informed of how to make the solution at home and of the importance of keeping hydration high while seeking care for people with cholera. With rapid and appropriate care, the case fatality rate should remain below 1%.

The OCV should be used in conjunction with improvements in water and sanitation to control cholera outbreaks and for prevention in targeted areas known to be at high risk for cholera. Risk communication and community engagement activities should be conducted to manage vaccine demand and raise awareness of vaccination campaigns. If a single dose schedule is being used, communication is needed to inform communities of why the dose schedule has changed and to share information on safety and efficacy.

WHO recommends Member States to strengthen and maintain surveillance for cholera, especially at the community level, for the early detection of suspected cases and to provide adequate treatment and prevent its spread.

As this outbreak is occurring in border areas where there is significant cross-border movement, WHO encourages the countries concerned to ensure cooperation and regular information sharing.

WHO does not recommend any restrictions on travel and trade to and from Mozambique.

Further information

- WHO Cholera factsheet

- GTFCC, Public health surveillance for cholera: Interim guidance

- ENDING CHOLERA, A GLOBAL ROADMAP TO 2030

- WHO Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 6: 30 January to 5 February 2023

- World Health Organization (11 February 2022). Disease Outbreak News; Cholera – Global situation. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON437

- World Health Organization (9 February 2023). Disease Outbreak News; Cholera – Malawi. Available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON435

Citable reference: World Health Organization (24 February 2023). Disease Outbreak News; Cholera – Mozambique. Available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON443