In the early days of the pandemic, WHO issued an urgent call to countries to ensure the continuity of services that prevent, detect and treat malaria for all in need. Together with partners, we developed guidance to support countries in their efforts to safely deliver critical malaria interventions within the context of COVID-19.

This year’s World malaria report spotlights an important and positive message: through the strenuous actions of malaria-endemic countries and their development partners, the worst-case scenario projected by WHO – a doubling of malaria deaths in sub-Saharan Africa – was averted.

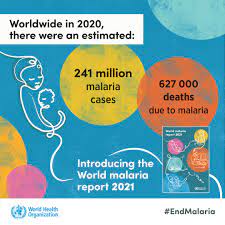

Nonetheless, the findings of our report are sobering. In 2020, 14 million more people contracted malaria, and 69 000 more died from it, than in 2019. About two-thirds of the additional deaths (47 000) were linked to disruptions in the provision of malaria services during the pandemic.

Global malaria cases and deaths, 2019–2020

/word-malaria-report/wmr2021-cases-deaths.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=52ebd1e0_14)

Progress had already plateaued pre-pandemic

As described in our report, the world was making good progress against malaria in the first 15 years of this century. The global case incidence (cases per 1000 people at risk) and mortality rate (deaths per 100 000 people at risk) fell by an estimated 27% and 51%, respectively, between 2000 and 2015.

But in recent years, forward momentum leveled off. By 2017, the case incidence rate ticked upward, and the decline in the mortality rate had stalled. In 2020, 24 nations actually saw more malaria deaths than in 2015, the baseline of the WHO Global technical strategy for malaria (GTS).

Of particular concern are the reversals in progress that we are seeing in countries hit hardest by malaria. In the 11 countries that shoulder approximately 70% of the global malaria burden, annual malaria cases fell from 155 million to 150 million between 2000 and 2015 and then increased to 163 million in 2020. Annual deaths followed a similar trajectory.

We are substantially off track in our efforts to achieve the malaria targets of the WHO global strategy. In 2020, the global malaria case incidence rate was 59 cases per 1000 people at risk against a target of 35 – off track by 40%. The global mortality rate was 15.3 deaths per 100 000 people at risk against a target of 8.9 – off track by 42%.

Comparison of global progress in malaria mortality, considering two scenarios: current trajectory maintained (blue) and GTS targets achieved (green)

/word-malaria-report/gts-worldwide-nl.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=1db9579a_8)

A new methodology

In this year’s report, WHO used a new methodology that provides more precise estimates of malaria’s death toll among children under 5 in sub-Saharan Africa. The methodology is described in detail in a recent article for The Lancet journal of Child & Adolescent Health and is being applied across WHO for all diseases.

Sadly, this more accurate picture is also a grimmer one: the new methodology reveals that malaria has claimed many more lives over the last 20-year period than previously recognized. Our new analysis shows, for example, that there were some 558 000 malaria deaths globally in 2019, nearly 150 000 more than earlier estimates.

The 2020 estimate of 627 000 malaria deaths reflects both the new methodology and the increases in deaths seen as a result of disruptions to malaria services during the pandemic.

Estimated number of deaths using new WHO methodology (blue) and previous methodology (grey), 2000–2020

/word-malaria-report/methodology-nl.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=32aea866_8)

A convergence of threats in Africa

Compounding the need for urgent action, a convergence of threats in sub-Saharan Africa could spark a resurgence of malaria if we do not act aggressively right now to contain the disease. These threats extend well beyond COVID-19 – from Ebola outbreaks and armed conflicts to humanitarian emergencies aggravated by climate change.

A number of other emerging threats could further jeopardize efforts to control the disease. Parasites that are partially resistant to artemisinin – the core compound of our most effective antimalarial medicines – have been detected in Rwanda, Uganda and elsewhere in East Africa. Malaria parasite mutations are reducing the effectiveness of our most commonly used rapid diagnostic tests, particularly in the Horn of Africa.

Mosquito resistance to the insecticides used in our primary vector control tools remains an ongoing cause for concern. And, in recent years, an invasive vector species that adapts easily in urban environments, Anopheles stephensi, has been extending its range in East Africa, with detections reported across Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia and the Sudan.

If the world doesn’t immediately respond with decisive action and resources, we are in danger of not only missing key 2030 global malaria targets but also of seeing this ancient menace re-emerge with devastating force. In short, we are facing an emergency on malaria that has been exacerbated by COVID-19.

First WHO-recommended malaria vaccine

In October 2021, WHO made a historic announcement: for the first time, the Organization recommended the broad use of a vaccine for children living in sub-Saharan Africa and in other regions with moderate to high P. falciparum malaria transmission. The recommendation was based on a review of the full package of evidence on the RTS,S vaccine, including results from a WHO-coordinated pilot programme that has reached more than 830 000 children in 3 African countries since 2019.

To date, the pilot programme has shown that the vaccine is safe, has substantial public health impact and is highly cost-effective. It is the largest implementation study that WHO has ever undertaken.

If introduced widely, we estimate that the RTS,S vaccine could save between 40 000 and 80 000 young lives every year – but only if it’s given a chance to work. We have just witnessed the rapid scale-up of safe, effective COVID-19 vaccines in many parts of the world. Children at risk of malaria deserve that same level of urgency.

Demand for the RTS,S vaccine is expected to be high, and supply in the near to medium term will be limited. Current vaccine production capacity stands at 15 million doses per year, while demand is estimated at more than 80 million doses annually. The recent funding announcement by Gavi is a big step in the right direction. On 2 December, the Gavi Board approved an initial investment of about US$ 155 million to support the introduction, procurement and delivery of the vaccine in sub-Saharan Africa over the next 3 years.

I cannot overstate the importance of these 2 announcements – first, the WHO recommendation, and second, Gavi’s decision to open a funding window for the vaccine. As I have said before, we need new tools in our malaria fight to reach global targets. And now, for the first time, we have a safe and effective malaria vaccine that can do what is most important in public health: avert deaths.

The RTS,S vaccine represents a scientific and public health breakthrough. It is not only the first WHO-recommended malaria vaccine, but also the first vaccine against a human parasite. RTS,S is also the first tool in our malaria toolkit that uses the human immune system to avert malaria infections and, in turn, their progression to severe disease and death.

Latest updates from malaria-eliminating countries

Although globally we are off track, a growing number of countries are moving steadily towards the target of malaria elimination. According to the latest World malaria report, more than half of all countries with ongoing malaria transmission (47) had less than 10 000 cases of malaria in 2020, up from 26 countries in 2000. Of these, 23 countries reported fewer than 10 cases of malaria in 2020.

Number of countries that were malaria endemic in 2000, with fewer than 10, 100, 1000 and 10 000 indigenous malaria cases between 2000 and 2020

/word-malaria-report/malaria-eliminating-countries-nl.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=4303bc44_7)

This year saw China certified by WHO as malaria-free – a stunning achievement for a country that reported 30 million cases of the disease annually in the 1940s. China is the first country in the WHO Western Pacific Region to be awarded a malaria-free certification in more than 3 decades.

Earlier this year, El Salvador became the first country in Central America to achieve a malaria-free status. The WHO certification is an impressive feat for a country with a dense population that shares open borders with 2 malaria-endemic nations.

On this year’s World Malaria Day, WHO joined partners in celebrating countries that are approaching, and achieving, malaria elimination. They provide inspiration for all nations that are working to stamp out the disease and improve the health and livelihoods of their populations.

In the lead-up to World Malaria Day, we published a new report highlighting successes and lessons learned among the “E-2020” group of malaria-eliminating countries. Despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, 8 E‑2020 member countries reported zero indigenous cases of malaria in 2020, and many others made impressive progress in their journey to becoming malaria-free.

Ahead of World Malaria Day, WHO also announced the launch of the “E‑2025”, a new elimination initiative that builds on the foundation of the E‑2020. A new set of 25 countries has been identified with the potential to eliminate malaria by the year 2025.

Global strategy refresh

In May 2021, the World Health Assembly, the main governing body of WHO, adopted an updated global malaria strategy. The strategy retains the goals and milestones endorsed by the Assembly in 2015 but is more closely aligned with WHO’s Thirteenth Global Programme of Work (2019–2023) and “Triple Billion” targets, as well as the global universal health coverage agenda, a key driver of the Organization’s work worldwide.

The Assembly also adopted a new resolution aimed at revitalizing and accelerating efforts to end malaria. Led by the United States of America and Zambia, and co-sponsored by many other countries, it urges Member States to step up the pace of progress against malaria through plans and approaches that are consistent with WHO’s updated global strategy.

The resolution calls on countries to extend investment in and support for health services, ensuring no one is left behind; sustain and scale up sufficient funding for the global malaria response; and boost investment in the research and development of new tools.

Consolidated guidelines for malaria

At the beginning of the year, we launched the WHO guidelines for malaria which bring together, for the first time, all of the Organization’s most up-to-date recommendations on malaria in a web-based platform. These consolidated guidelines are a “one-stop shop” for WHO guidance on malaria, superseding all previously published documents.

Through the platform, users can access the evidence that underpins each WHO recommendation and there is a feedback tab to help identify recommendations that may need an update or further clarification. Inputs from our stakeholders are also welcome by email at: [email protected].

In 2021, 4 WHO guideline development groups focused on vector control, chemoprevention, treatment and elimination convened to develop new or updated recommendations. WHO’s recommendations on malaria will continue to be updated, where appropriate, based on the latest available evidence through a transparent and rigorous guidelines review process.

In recent years, WHO has been advising countries to move away from a “one-size-fits-all” approach to malaria control – applying, instead, an optimal mix of tools tailored to local settings. As such, the WHO guidelines for malaria are not intended to be prescriptive. Countries are encouraged to use local data to identify recommendations that are relevant to the local context. By adopting a more targeted, data-driven approach, countries can maximize available resources while ensuring efficiency and equity in malaria responses.

The consolidation of WHO’s malaria guidelines is one of a number of actions we have taken to make our guidance more accessible to our primary audiences in malaria-endemic countries. All WHO recommendations are also available through an easy-to-navigate mobile app; we encourage you to download it if you haven’t done so already. And, in recent months, we have started developing short, animated videos to describe our guidance across a range of technical areas; the first video, as you will see below, addresses the issue of HRP2 gene deletions.

Source WHO