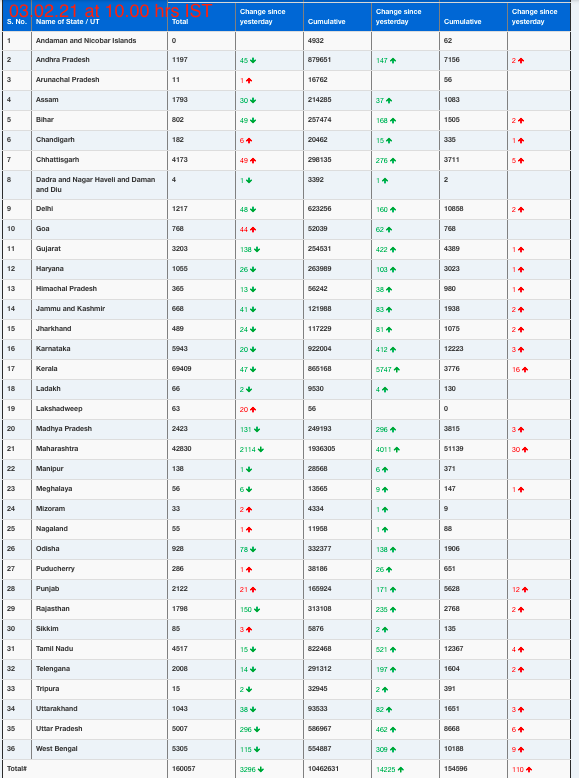

An average of over 73,000 people were treated, every year, for 3 years with a total of 221,308 treatments. Adults and children over 5 years of age were included. The outcome was a significant reduction in the prevalence of taeniasis, observed four months after the last mass treatment of communities in the villages.

“The lessons from this important project and its impact go beyond Madagascar” said Dr Bernadette Abela-Ridder, in charge of WHO’s Neglected Zoonotic Diseases programme. “They show that if we treat people with the right dose at regular intervals, few will get infected or develop neurocysticercosis.”

However, this reduction could not be maintained, and sixteen months after the last treatment, taeniasis returned to its original levels, but the outcome of the pilot project implies a ‘One Health’ approach3 is required to break the cycle of infection. This can effectively happen when regular treatment of people living in endemic areas is combined with pig vaccination and pig treatment.

Picture: WHO / People in one of the 52 villages in Madagascar’s Antanifotsy District waiting to be treated with praziquantel against taeniasis during a pilot project that ran from 2015-2017

The project, led by the Ministry of Health of Madagascar and supported by the World Health Organization (WHO), started in 2015.

Taeniasis is prevalent in rural areas of Madagascar where people practice backyard pig rearing. The parasite that causes taeniasis, T. solium, was first described in the early 1900s in Madagascar.

Taeniasis/cysticercosis

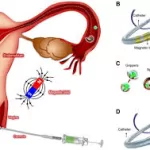

Taeniasis – an intestinal infection caused by T. solium tapeworm – occurs when humans eat raw or undercooked, infected pork.

People who have tapeworms in the intestine will shed tapeworm eggs.